![]()

HISTORY OF BINGHAM

GEORGIAN BINGHAM

With the accession of George I in 1714, Great Britain was ruled by a King George until 1820. Bingham in this period was a small market town with a population that rose from around 550 in 1674 to just over 1000 in 1801, mainly in the last quarter of the 18th century. It then expanded rapidly to 1,326 by 1811. Described in 1813 as ‘now nothing but an inconsiderable straggling place’, over 80% of the property was owned by the absentee Earls of Chesterfield and managed by their local land agent.

Bingham retained its status as the head of both the Bingham Hundred (or Wapentake), an administrative sub-division of the county, and an ecclesiastical Rural Deanery. Justice and local administration was exercised by magistrates, who held petty sessions courts every fortnight in the Royal Oak (which became the Chesterfield Arms in 1812).

Bingham was essentially a farming community and most farmhouses were still in the town centre as they had been in Elizabethan times, largely on Husband Street (Long Acre) and the modern East Street respectively. A small weekly market was still held around the original Butter Cross in the Market Place, but dealing mainly in butter, cheese and garden produce rather than corn and livestock. Rising population and subsequent food shortages at the end of the 18th century led to an increase in arable production and resulted in three windmills appearing on Sanderson’s map of 1835, the most prominent being situated at the top of what is now Tithby Road.

However, although situated on the eastern edge of the Nottinghamshire hosiery district there was also a substantial community of stocking framework knitters, who knitted stockings on hand-and-pedal-operated machines in workshops inside or attached to their cottages. In 1793 there were with six named master stockingers.

Communications were improved by the introduction of turnpike toll roads. The roads from Nottingham to Grantham and from Saxondale to Newark were turnpiked in 1759 and 1776 respectively. The first had a tollhouse at the end of Granby Lane on the Grantham Road and the other had one on the Fosse Road (now Buggins Cottage). By 1822 the Nottingham to Lincoln coaches were calling daily at the ‘Chesterfield Arms’ in Church Street. However a projected branch of the new Grantham Canal (opened 1797) to Bingham was never built, leaving the town two miles from the nearest wharf at Cropwell Bishop.

Bingham people

The first trade directory to mention Bingham was published in 1793 and listed over 100 names. The range of trades reflects those of most country towns of the period – butchers, bakers, shoemakers, tailors, wheelwrights, coopers, smiths and the rest. However there were also a surgeon/apothecary and a druggist, a glass dealer, and even a peruke (wig) maker. Newspapers from the second half of the 18th century make reference to a cutler, milliner and cordwainer, who made shoes and other goods is soft leather. Mr John Pilgrim of the Royal Oak advertised his fine wines and spirits and assured travellers of genteel accommodation and Mr Scoffings, a shoemaker, advertised that he makes and sells ‘ladies’ shoes with Italian and French heels, in various colours in silk or calimanco*’. Three ‘bricklayers’ i.e. builders, are listed, as by this time brick was becoming increasingly used.

* calimanco is a glossy woollen fabric chequered or brocaded in the warp so that the pattern shows on one side only; popular in the 18th century.

Several broken wig curlers were found at the site of the 18th century village dump.

The newspaper articles from 1765 onwards repeatedly show a strong sense of community and social responsibility among the wealthy townspeople. There was no shortage of them. Well off businessmen and women, men of private means and rich tenant farmers all lived here. The Porter family, who lived in Bingham until c1754, were significant freeholders with a large house and estate. In the newspaper notices for the 1770s and 1780s there are several mentions of opulent or wealthy farmers or graziers or both. Among them are William Hutchinson, Richard Skinner, Thomas Pacey, John Chettle, John Timms and William Moggs. John Needham is described as “a gentleman of large fortune”; John Bradshaw as ‘a gentleman and High Constable of the North Division of Bingham Hundreds’; William Brookes as a gentleman ‘skilled in Philosophy and Polite Literature’; Henry Andrews, as ‘a gentleman, a writer of verse and prose’; Mr Daniel Stafford, as ‘an Astronomer, Schoolmaster and compiler of Almanacks for the Worshipful Company of Stationers’. Of Mr John Bates it was said, ‘formerly a plumber and glazier, but of late retired having acquired a handsome fortune.’ Richard Oliver was a maltster of ‘Great business’.

Staffordshire Slipware dish with pie-crust rim, 33 cm in diameter. This was very popular in the first half of the 18th century. NCM 1993-729/42 Nottingham Brewhouse Yard Museum.

A brown-glazed slip-coated pancheon, 43 cm diameter at the rim, typical of the kind that would have been found in the dairy or kitchen in the 18th century. In Bingham the commonest kind had a black glaze. NCM 1966-170/60 Nottingham Brewhouse Yard Museum.

William III silver sixpence minted in 1696. This is one of the earliest milled edge coins. It remained incirculation throughout much of the 18th century

A copper halfpenny token for the Associated Irish Mine Company in Cronebane Ireland. These tokens, minted in Birmingham between 1789 and 1796, were commonly used in England when legal copper coinage was in short supply.

Fragments of Nottingham made brown stoneware showing typical decoration. Nottingham was an important centre for the manufacture of stoneware from around 1690 to near the end of the 18th century making everything from kitchen ware and table ware to novelties.

Bingham’s parish church was served by a rector who enjoyed the profits of the wealthiest living in Nottinghamshire. A newspaper advertisement on 8th July 1784 for the living at Bingham rectory claimed that the rector had an income of more than £600 a year from tithes. From 1764 to 1810 the rector was the Reverend John Walter, who in 1771 built himself a large new rectory house (demolished 1964). He was however unpopular and for some 30 years was at war with the majority of his parishioners, being personally involved in no less than eight lawsuits with them over this period.

The Rectory, built in 1771, was demolished in the 1960s to make way for the Robert Miles junior school. It was the place of birth of Robert Lowe, Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1868 to 1873, and the home of the rector, Canon Robert Miles, from 1845 to 1864. It was visited by Oscar Wilde and Lily Langtry, friends of his son, the artist Frank Miles. Photo by permission of Rose Whittaker.

Bingham farming in 1776

The survey of the Chesterfield estate carried out in 1776 provides the first look at Bingham after enclosure in 1680-90. It noted but gave no detail about the land owned by the freeholders, of which the Porter family was still the largest. It appears that after enclosure the Earl of Chesterfield retained no land for his own use. All 2446 acres were rented out to 68 tenants. Of these there were 10 with 100 or more acres. John Hutchinson, with 265 acres had the largest holding.

Before enclosure it was customary for each tenant to have strips in all or most of the furlongs, so their holdings were spread all over the parish. This custom remained after enclosure with most of the tenants having widely spread out fields, partly so that they could have a share of the pasture and meadow that was largely in the north of the parish and as well as the traditional good arable land in the south (see Map 2). ( Link to Map 2 in 1776 section of Old Maps) However, there were four holdings where all the fields were contiguous (see Map 1). (Link to Map 1 in the section on 1776 in Old Maps) These were the beginnings of the three modern day farms – Holme, Brocker and Starnhill. In each case a house existed there in 1776. John Hutchinson was the tenant at Starnhill Farm, which was in the middle of a large area that was converted to pasture in the late 16th century. On the western side of this area are Rams Closes, suggesting that he was a sheep farmer. The fourth block was rented by George Bradshaw and was also in what is now Brocker Farm, but had no house with it. John Timms jnr almost managed to concentrate his holdings, having only three small closes a little way from his main group of fields, but still lived in the town. Thus the first steps had been taken in a process of dispersal of farmhouses from the village to the countryside and the consolidation of blocks of land for each farm that took until the 1960s to complete

Not all the tenants were residents of Bingham. One came from Whatton; others from Cropwell Butler (see Map 5). (Link to pop up 11, Map 5 Occupiers probably not resident in Bingham in 1776 section on Old Maps)

A number of closes were shared tenancies. Some were land that in 1586 had been common grazing and there is some evidence that this arrangement did not end until after 1776. Others were individual closes created in 1680-90 that were shared between 2 to 4 tenants. These are less easy to explain.

Bingham town in 1776

The layout of Bingham was still essentially the medieval town, but while most properties were still on what is now Long Acre/Long Acre East and the northern back street Newgate Street eastwards to East Street, there were now some on the linking lanes. At some time after 1586 the churchyard was extended across East Street, effectively isolating East Street from Church Street. This must have had a significant impact on Bingham because it destroyed one of the through routes.

A number of present day buildings in the town date from the late 18th century. These include the Chesterfield Arms, as well as nos 9, 11, 15b and the rears of nos 19 and 21, Church Street, and the Wheatsheaf Inn, Falcon House and Regency House all in Long Acre. Several more have 18th century origins but with 19th century additions or frontages. Many of the houses from that period must have been demolished since and replaced. There is evidence for this in the 1776 survey, which identifies the homesteads of the main farmers. (Link to pop up 12, map Bingham Town 1776 Location of major farmhouses) In some cases there is nothing left other than renovated barns at these sites.

The Wheatsheaf as it is now is a classic late 18th century East Midlands design with small third storey sash windows. The date 1792 on the front may have been when the building was modernised. References to the pub in late 18th century newspapers show that it was in existence before 1792.

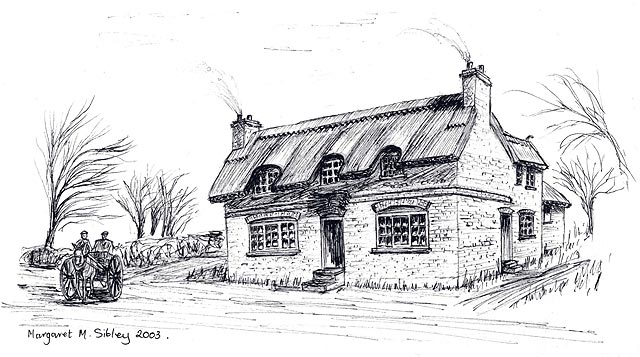

The western wall of the Wheatsheaf shows an upward change in brickwork suggesting that it was originally a two-storey building. This artist’s impression by Margaret Sibley is an attempt to interpret what the pub may have looked like in the mid 18th century.

In a survey of 1776 eleven houses are recorded as ‘on the waste’ and were no doubt squatters’ cottages. Six were on the south side of The Banks and these were the only houses there. Three were north of Fair Close on Newgate Street. Waste land was owned by the lord of the manor, usually on town greens or wide grass verges etc. Although technically these were illegal encroachments the lord often allowed them to remain in return for a nominal payment.