![]()

HISTORY OF BINGHAM

Buildings at Margidunum

At least 22 buildings are known from Margidunum dating from the first to the fourth century. They were revealed during excavations carried out in the 1920s by Felix Oswald and in the late 1960s by Malcolm Todd. Some of these buildings were represented merely as floors of beaten clay whereas for others wall footings survive. In contrast to sites in Italy where Roman houses survive still standing, very few buildings of the Romano-British period survive above ground level. This is due to a combination of neglect, collapse, weathering, stone robbing and plough damage. An antiquarian, William Stukeley, visited the site of Margidunum on the 7th of September 1722. He records in his Itinerarium Curiosum, published in 1724, that he saw “Roman foundations of walls and floors of houses, composed after the manner spoken of, of stones set edgewise in clay, and liquid mortar run upon them: there are likewise short oaken posts or piles at proper intervals... Houses stood all along upon the Foss, whose foundations have been dug up and carried away to the neighbouring villages... close by has been a great building, which they say was carried all to Newark.”

Felix Oswald put aside a room at the University where he studied and displayed the Margidunum finds. Here he is studying one of the complete pots (probably from one of the many wells he excavated). He was the first person to study Margidunum in the modern period.

Original picture in the Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Much has clearly been lost since the Mediaeval period. Nevertheless it is possible to piece together a picture of what the houses may have looked like from evidence left behind by the stone robbers such as fragments of columns and tiny scraps of marble veneer. Although we no longer have the superstructure intact areas of fallen daub, broken up painted plaster, window glass, and roofing tile all help us to reconstruct the nature of the houses. Under-floor elements such as hypocaust systems (the Roman central heating system) provide additional evidence for the type of building excavated. Some further light comes from evidence from preserved building elsewhere in the Empire, from Classical accounts of building techniques and from the excavation of other buildings in Britain.

The curving infilled gully found at Margidunum is thought to have been made by dripping water off the thatched roof of an early roundhouse. Photo: M. Todd. Nottingham University Dept Archaeology (No B1642)

Before the Romans arrived

A curving gully found in a trench excavated within the defensive ditch of Margidunum compares well with the sort of archaeological remains left by the round houses, which were so common in the Iron Age settlements of the Trent Valley and continued to be used well into the Roman period. Given that the fine character of the finds suggests that the earliest Roman phase of settlement at Margidunum is likely to be military in character, this type of gully is more likely to belong to a very early phase before the military arrived.

Very little evidence for pre-Roman occupation of the Margidunum site was noted by Oswald or Todd, but excavations south of the defences of Margidunum by Trent & Peak Archaeological Unit revealed evidence for activity near the site in the late Iron Age.

First century buildings

Foundations and flooring

Excavation has revealed slots and gullies associated with occupation in the area in the first century AD. These slots, dug through the natural clay, were identified because of their darker fill and are all that remains of the slots dug to hold the timber uprights. In only one case did the “ghost” impression of one of these posts survive. Some of these slots may have held planks into which upright post were then inserted or, in some cases, the upright posts were put directly into postholes and the postholes were then packed with other material. Some gullies may represent the effect of water run off from the roof of a building and may not be structural at all. A rectangular building with at least two rooms, measuring 12 ft x at least 24ft, was excavated by Todd and there were fragments of two more possible buildings, one of which had a post impression.

What did the early houses look like?

Evidence for the superstructure and some embellishment of these early buildings survived and were recorded by Oswald, who found “charred beams ..and many fragments of burnt daub” underneath one of the later buildings he excavated (building L) and post-holes associated with floors paved with slabs of skerry stone.

Skerry is the common name for a kind of sandstone found in the Triassic bedrock of Nottinghamshire. The sandstone is made up mainly of the minerals quartz and calcite. It is very hard and forms thin beds, rarely more than 3 to 4 inches thick. It breaks into flat slabs that can be shaped and sized for building and was used in the lower courses of the walls of houses and farm buildings into the 18th century.

Oswald suggests that the site of this last building had been carefully prepared by levelling with quantities of sand, probably because it was a marshy area but alternatively an area of ground covered by natural sand drift may have been chosen by the builders. In contrast to this, the area occupied by building L seems to have been prone to becoming boggy and was abandoned at the end of the second or early in the third century when it was sealed with sterile marsh silt. Although none of the plans of these early buildings in the area of building G excavated by Oswald can be recovered, his account together with the quantity of first century pottery and plaster associated with some sections of the earliest paved surface indicates the possibility of a stylish early house on this site. Todd points out in his review of Oswald’s excavations that some of the earliest paving dates to the end of the first century or as late as 125AD but the coin he uses as dating evidence comes from below paving south of the complex of walls and postholes so a later date for the paving has not yet been demonstrated.

Slots and gullies that

may have been dug to hold timber uprights and planks

in a early building

Photo: M. Todd. Nottingham University Dept Archaeology

(No B1384)

When the Romans first arrived in Britain most buildings were made entirely of timber, with the exception of bathhouses in which uncovered timber would constitute a fire risk. The existing evidence from Margidunum suggests that buildings here were timber framed with an infill of wattle and daub. Such buildings may have been thatched or covered with wooden shingles. They were susceptible to destruction by fire, as seems to have happened in some cases at Margidunum, and a Roman writer, Vitruvius, writing in the first century BC, advises: “As to wattled walls, would they had never been invented, for though convenient and expeditiously made, they are conducive to great calamity from their acting almost like torches in case of fire. It is much better, therefore, in the first instance, to be at the expense of burnt bricks, than from parsimony to be in perpetual risk. Walls moreover, of this sort, that are covered with plaster are always full of cracks, arising from the crossing of the laths; for when the plastering is laid on wet, it swells the wood, which contracts as the work dries, breaking the plastering. But if expedition, or want of funds, drives us to the use of this sort of work, or as an expedient to bring work to a square form, let it be executed as follows. The surface of the foundation whereon it is to stand must be somewhat raised from the ground or pavement. Should it ever be placed below them it will rot, settle, and bend forward, whereby the face of the plastering will be injured. II.8.20.”

In Britain wattle and daub houses are thought to be by far the most common type, probably because of the ready availability and cheapness of timber and the relatively high cost of quarrying and preparing suitable stone.

The evidence of collapsed building debris

Fragments of building debris associated with pottery of this early period included a fragment of a millstone grit arch or window and window glass. Some complete roof tiles in Nottingham University Museum are recorded as coming from a well dating to the mid to late first century. These fragments allow us to reconstruct at least one building with stone elements, a tiled roof and window glass. This is very likely to be a bathhouse since these commonly had glazed windows to keep in the heat and tiled roofs to lower the risk of a conflagration of the roofing material.

Fragments of window glass were found

in both of the large-scale excavations at Margidunum and show that at least

some of the houses had the luxury of glazing. According to Roman writers, windows

were only available to the wealthy. Window glass was made by pouring molten

glass onto wooden trays and leaving to harden. The windows would have been quite

opaque compared to modern ones.

Nottingham University Museum. Photo: Robin Aldworth

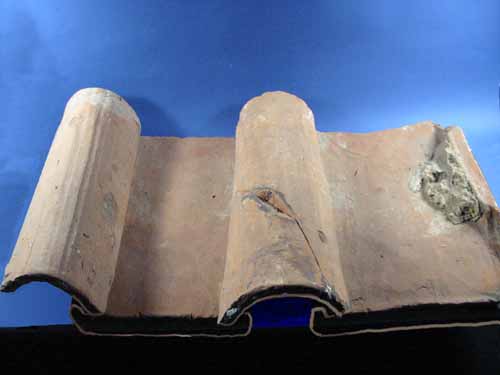

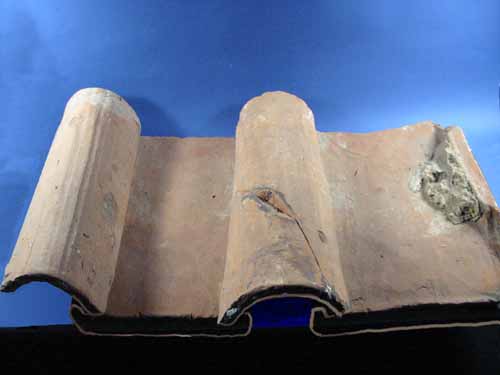

Roman roof tiles, showing how they were

used. Note the concrete visible to the right.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth.

Click here to see a reconstruction drawing of Roman bathhouse at Slack Fort, Yorkshire.

Click here for a reconstruction of how bathhouses worked.

Second century buildings

Changes in construction techniques

Rather more is known of the buildings dating to the second century. At least nine buildings were erected during this time along the Fosse Way (itself dating from the late first century) and all of these had stone footings, made from the local skerry stones. Buildings with stone footings are very common in Roman Britain and it is often difficult to reconstruct the superstructure. Guy de la Bedoyere concludes that most of these had timber-framed superstructures. The bathhouses are likely to have stone superstructure because of the fire risk in timber structures.

Five or six methods of construction were

used to build the stone-footed buildings:

1. In buildings G, H, I and J wall trenches filled with skerry

rubble loosely packed.

2. In building

C wall trenches filled with closely packed skerry lumps

between two rows of facing block of skerry.

3. In building D wall trenches were filled with pitched skerry

slabs. This technique was used to consolidate part of

the wall of building J where it ran over an earlier pit. A

second example of pitched footings with no mortar was found

beneath the town rampart.

4. In the undated building F a section drawn by Oswald records

a wall trench filled with stone slabs set on edge with mortar

at the bottom.

5. In building L Oswald found pitched skerry stones set into

clay with two courses of flat stone slabs remaining above

and in building M Oswald records that the wall trenches still

contained several horizontal courses. These may be more intact

examples of type 3.

6. The east wall of building L had been constructed slightly

differently with a thicker wall (c1foot wider) set in concrete.

This may have been constructed to take a heavier superstructure

such as a tall facade.

Remains of Building C showing how skerry

stone was used in the foundations.

Photo: M. Todd. Nottingham University Dept Archaeology (No B1798)

Pitched slabs of skerry in a wall trench

in building D.

Photo: M. Todd. Nottingham University Dept Archaeology (No B1408)

Although the Romans were skilled builders and architects with instruction books, such as Vitruvius’s manual mentioned above, and tools for surveying, building work in small towns and rural settlements was sometimes rather haphazard and even “bodged”. At Margidunum the builders of at least two of these houses were forced to make provision for possible subsidence because of encountering the unstable infill of earlier pits. In both cases the wall foundation trenches were deepened to bottom the pits and the wall trenches were filled with carefully alternately pitched skerry slabs to prevent later subsidence and instability.

What did the town houses look like?

Rather more evidence for the appearance of these second century buildings has been excavated. Some buildings, such as those fronting the Fosse Way (buildings H, I and J), had simple floors of beaten clay whereas other (building G) had areas of skerry paving. These were probably simple workshops and traders stalls with resident blocks at the back or, possibly, in an upper story. These are common in Roman roadside settlements. The occupants of Building C aspired to rather more durable flooring: paving in some rooms and elsewhere a mixture of mortar, clay and earth. This embellishment, together with the neatly faced wall footings may reflect a higher social status.

Remains of Building C showing how skerry

stone was used in the foundations.

Photo: M. Todd. Nottingham University Dept Archaeology (No B1798)

Remains of the floor of

Building C

Photo: M. Todd. Nottingham University Dept Archaeology

(No B1638)

The building also had three rooms, contrasting with the single apartment life style of the pre-Roman roundhouse dwellers and some of the other inhabitants, and was set back from the road. This house also has evidence for a back yard and the convenience of a large water tank situated just outside. Evidence from this building is rather better than from some of the other houses but it does seem to stand out as being rather more affluent.

Water tank outside Building C

Photo: M. Todd. Nottingham University Dept Archaeology (No B1799)

A “motel” for Roman officials?

The most elaborate buildings are L and M (the bathhouse). Neither of these is likely to be a private, domestic building, but they may have been used by travelling Imperial officials as well as the townsfolk. Building L is very large with no signs of subdivisions. Oswald recovered evidence of a concrete surface covering the outside area to the north and overlapping the foundations suggesting it abutted a timber-framed wall of some sort. The interior was covered with several phases of gravel floors. Wall plaster fragments were found interleaved with these gravel floors indicating this building was probably plastered. Painted fragments of wall plaster from under the lowest floor identified by Oswald tells us that this level of sophistication was present at or near the site of this building from an early date. Oswald identified an area of concrete surmounted by a plaster of Paris base which he though could be a base for a statue. This base still had impressions of the wooden framework used to make it. It is uncertain what this building is but it is likely to have had a public function, perhaps with a religious element.

A box flue tile. These ducted

hot air from the underfloor heating system up the walls

to let the steam out the eaves. They were used in bath

houses to heat up the warm rooms. This example has traces

of wall plaster still adhering.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

The neighbouring building, M, is a bathhouse. This had two types of under-floor heating: a floor raised on brick pillars and a floor with channels lined with tile built into them for the hot air to travel along. The floors were made of a special Roman concrete, opus signinum, made from concrete mixed with crushed brick and tile. This was a durable choice in the steamy atmosphere of the baths and reduced the risk of fire. Debris from the collapse of the bath building included box flue tiles, roofing tiles and wall plaster. A white mortar floor was found by Oswald below the opus signinum floor of the bath suite and this, together with the painted plaster in the early levels of building L, suggests there was an elaborate building on or near this site before either building L or M were built, perhaps an earlier bathhouse. We can suggest that building M had a stone wall, rather than a timber frame, to hold up a tiled roof and not catch fire. The walls would have been painted and the windows were probably glazed.

Roman roof tiles, showing how they were

used. Note the concrete visible to the right.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth.

This piece of painted plaster gives

a tiny glimpse of the splendour of some houses at Margidunum. The wall paintings

have fallen off the walls as the building fell into disuse and, sadly, the weather

and the plough have broken up the fragments over the centuries so that it is

no longer possible to reconstruct the full design. Enough remains to suggest

coloured borders and stripes with some patterns.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

A well in the area of building G contained a fragment of a small column of Lincolnshire limestone. This had a flattened back and a rectangular notch cut in the upper side suggesting it was used as a pilaster (column fitted against a wall) decorating an elegant house. This fragment was found in a rubble layer between groups of pottery, which would indicate a date in the earlier Roman period, perhaps as late as the 2nd century. We do not know which building this pilaster may have belonged to but it does indicate the adoption of classical styles by one of the inhabitants.

Third to Fourth century buildings

Margidunum citizens prosper?

The Roman name for Margidunum means marly fort and there is much evidence in the area of the excavations and in later records that the site was situated on a small rise in an area of flat marshland. The area occupied by buildings L and M was close to a damp depression within this area and the buildings seem to have been flooded during the third century. Sometime around the middle of the third century, large stones were used to consolidate the area above the silted-up remains of buildings L and M and a gravel layer was laid down. A large, well-appointed stone-footed building (N), surrounded by this gravel layer, was found by Oswald to the south of buildings L and M. It had floors of opus signinum (Roman concrete) and plastered walls decorated with grey panels and bands of red, orange and green. Oswald noted a plaster quarter moulding had been made at the junction of the walls and floors. He also found the plaster in situ on the walls. A large number of Charnwood roof slates were recovered from this building with nail holes in them, which would result in a diamond pattern when laid. This building was aligned with buildings L and M and although Oswald dates it to the fourth century, the complexity of the plan suggests alterations and rebuilding over a longer period of time, perhaps overlapping in use with these other buildings. A more modest building (B) east of the Fosse Way was found above the first century timber houses. This was built using the dry rubble type of stone foundation and had a beaten clay floor.

This piece of painted plaster gives

a tiny glimpse of the splendour of some houses at Margidunum. The wall paintings

have fallen off the walls as the building fell into disuse and, sadly, the weather

and the plough have broken up the fragments over the centuries so that it is

no longer possible to reconstruct the full design. Enough remains to suggest

coloured borders and stripes with some patterns.

Nottingham University Museum Photo: Robin Aldworth

Remains of a beaten clay

floor and dry rubble-type of stone foundation in Building

B

Photo: M. Todd. Nottingham University Dept Archaeology

(No B1402)

Sherds of colour-coated ware dating from 150 AD at the earliest was found below this floor but many sherds of late third to fourth century pottery overlay it. The date of this building is therefore sometime after the mid-2nd century and possibly as late as the late 3rd-4th. In style the house resembles the buildings that are dated to the second century. We know that a building of higher status existed near to this building as a thick layer of broken opus signinum was recovered from just south of it. This may be the source of the late 3rd-4th century pottery found above the floor of building B.

Other elaborate buildings of the late 3rd-4th centuries are known only from building debris found above earlier features. These layers of painted plaster and opus signinum with late 3rd-4th century pottery, were recorded by Oswald in a layer above the consolidated silts overlying buildings L and M, but below the gravelled area around building N and the rampart ditches. In the backfill of a well, which fell out of use and was used as a handy rubbish pit, roof tiles were found in a layer above debris containing late 3rd century coins. Although these tiles may be from a building first constructed in the second century, it does not seem likely that the tiles from first century buildings would be dumped in a well in the late 3rd century. Pryce, a co-worker of Oswald’s, mentions finding “isolated tessera” (small, square piece of a tile or other material used for making mosaic floors) and these are most likely to belong to a building with at least one mosaic or tesselated pavement.

Skerry paving floor

of a simple house, built late in the Roman period

or after it.

Photo: M. Todd. Nottingham University Dept Archaeology

(No B1627)

The collapse of civil order at Margidunum?

The latest structure discovered at Margidunum is represented by an oval patch of skerry paving associated with six large postholes. This was found to overlie the upcast bank of the town defences and was dated by pottery to after the mid-4th century. There is, however, no record of pottery associated with its occupation and such a simple hut may date to the very end of the Roman period or even the early Saxon period. It represents a real fall in living standards and its position over the rampart implies that the civil authorities were no longer able to take care of such public works.

Additional information on Margidunum

Reports on the excavations carried out by Oswald and Todd and of investigations in the area by Trent and Peak Archaeological Unit contain much of the detail on which this account has been based. The main sources are:

1 Trent & Peak Archaeological Unit. Archaeology

of the Fosse way. Vol. 2 (held by Nottinghamshire Sites and Monuments

Records).

2 Todd, M. 1969. 'The Roman settlement at Margidumun. The excavations

of 1966-8'. Transactions of Thoroton Society 72.

3 Oswald, F. 1927. Margidunum. Transactions of Thoroton Society 31, 55-84.

4 Oswald, F. 1941. Margidunum. Journal of Roman Studies 31, 32-62.

5 Oswald, F. 1948. The Commandant’s House at Margidunum. University

of Nottingham.

6 Oswald, F. 1952. Excavation of a Traverse of Margidunum. University

of Nottingham.

7 T.D. Pryce. 1912. Margidunum: a Roman fortified post on the Fosse Way.

Journal of the British Archaeological Association 177-210.

There are many web sites with information about Roman Britain. Links to some are given in the text. For books on the subject log on to http://www.english-heritage.org.uk and check their catalogue.