![]()

ENFORCEMENT OF THE LAW

Throughout the last 1000 years, the people of Bingham have been heavily involved in hunting out miscreants and administering just desserts to them through the law.

Hue & Cry – posse comitatus

The roots of local responsibility for crime prevention seem to lie in Anglo-Saxon customs that placed prevention squarely on the local community through the tithing and the “Hue and Cry”. Every male over the age of 12 had to belong to a group of nine others, called a tithing. These ten men were responsible for the behaviour of each other. If one of them broke the law, the others had to bring that person before the court. The sanction, to make the system work, was that if they did not, they would all be held responsible for the crime. This usually meant paying the victim of a crime for their loss. The community was also responsible for doing their best to chase after a criminal. Anyone wronged could call upon everyone else in a community to chase a criminal simply by calling on them to do so by “raising the hue and cry” – calling out for help. Everyone nearby was then supposed to join in the chase. If they did not make an effort then the whole community was held responsible for the crime and would face punishment themselves.

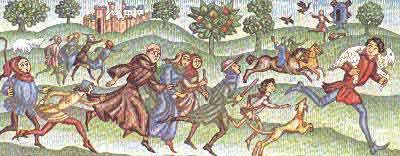

Chasing the sheep stealer. |

If the criminal got away, the king’s representative, the sheriff, could raise a posse comitatus to chase a criminal. Anyone called upon to join it had to do so.

Many of these customs were continued after 1066 by the Norman rulers, who needed a system to control the largely Anglo-Saxon population. It was obviously well suited to a time when there were few government officials and everybody knew everybody else in small, stable, local villages. The growth of towns in the later Middle Ages brought some changes, but even then each “ward” or area of a town was expected to react to the “Hue and Cry” just like a village community. Such officials as were appointed were responsible to the town government and were often part-time.

Introduction of constables, beadles and watchmen

This community-based, “hue and cry” system continued for some time after the Norman Conquest, but by the later Medieval period new systems were needed. Towns were growing too big for it to work and these larger communities had to appoint their own officials called, in different places, constables, watchmen or beadles (see paragraph below), to keep the peace. The constables would quite often supervise others whose responsibility was to guard the community gates at night. They were unpaid and were elected from local men. On the whole they were chosen from respectable tradesmen, craftsmen and shopkeepers, not ordinary labourers and contrasted in this way with the Justices of the Peace. They served for one year only.

Petty Constables

The job of the petty constable was to arrest criminals and to carry out instructions passed down from the JPs or the County Assize Justices. This could be awkward, as the petty constable found himself having to report on, even arrest, his neighbours. For this reason, they often used their discretion in applying the law and could get into trouble with higher authorities as a result. However, most petty constables did their duties as best as they could, alongside their full-time employment.

Watchmen had long been employed by local communities in towns to patrol the streets at night. Each one had a lantern and a stick and traditionally called out the hours and the weather. Because they were regulated by an Act of Charles II, they were known as “Charleys”

Watchman in the mid 16th century |

A major late Medieval threat to law and order was

the “over-mighty subject” – lords who used their private

armies to terrorise local villages. The community-based crime prevention

system was too weak to deal with them.

From the earliest times of parish management in Bingham a constable or

constables were appointed as local representatives of the law. They were

chosen annually by the vestry, a representative meeting of local interests,

and were directly responsible to the Justice of the Peace – in Bingham’s

case a local squire such as the Hildyards of Flintham Hall or the Nortons

of Elton. The constable’s functions were many and varied. He had

to check the licences of beer houses and convey out of the parish undesirable

paupers who might become a charge on the rates. Vagabonds, hawkers or

disturbers of the peace were to be arrested and imprisoned in the lock-up;

the collection of taxes was to be supervised, the parish pinder, or collector

of stray animals, was to be appointed and his duties overseen. This was

onerous by any standards but when the appointment was ‘voluntary’

and his permanent occupation had to be carried on at the same time, it

is not surprising that the constable was not immediately on the scent

of an incident. Such a weakness in the system was, of course, exploited

by the malefactor and by the 1840s local people were accustomed to acting

on their own initiative in the apprehension of criminals, and had even

formed a vigilante group – The Bingham Association for the Prosecution

of Felons (see below) – in an effort to reduce the number of crimes

committed locally.

In the eighteenth century Bingham Hundred had its

own Chief Constables:

1720 John Oliver of Aslockton died1723

1723 Joseph Mayfield of East Bridgford discharged1728

1728 William Flower of Granby

1759 Henry Flower died1772

1772 George Bradshaw of Bingham

1774 John Bradshaw of Bingham died1778

1778 John Strong of Bingham

The Police

During the 18th century the system of constables fell into disrepute and by the end of it, with the populations of the cities on the increase, the problem of local crime was so bad that the constables were unable to cope. Quite often the militia were called in to quell major disturbances.

In 1829 Sir Robert Peel introduced a civilian body in London to maintain law and order. It was called the Metropolitan Police. A new non-military uniform was designed and the officers were equipped with no more than a wooden staff to protect themselves and keep the peace.

In 183l the Special Constables Act gave the Justices of the Peace power to conscript men as Special Constables when required by threat of riot. However, in 1835 the Municipal Corporations Act was passed, which required every borough to appoint enough paid constables to police the borough effectively.

In 1848 the Bingham vestry appointed four constables in an attempt to combat an increase in crime, but help was on hand from the Nottinghamshire county police force, a body that grew out of Sir Robert Peel’s London ‘bobbies’ or ‘peelers’ through the 1839 County Police Act.

Nottinghamshire had taken advantage of this early. An officer, George Thursby, aged 20, is listed in the 1841 census returns for Bingham, together with William Gilman the local constable. William Gilman must have enjoyed his work for later he joined the police force and was stationed in Bingham in 1851. The Old Court House in Church Street, was built in 1852 as a courthouse, but also provided accommodation for the officer in charge. By 1855 this building was the headquarters for an inspector – Francis Poole – and six men. After this time the number of officers declined to a regular three – an inspector or superintendent being resident at the station, while the constables set up house in town or occasionally boarded with their superior. The senior officers moved on regularly, but the constables became more permanent members of the community, often being born outside the county, but marrying Bingham girls. To begin with the constables were not professionally trained men but could be recruited from any trade, bar those of gamekeeper, bailiff, hired servant, inn or beerhouse keeper, and were paid (1840) 16s per week. At the same time a superintendent would earn £75 per annum. By 1888 an inspector received £165 per annum

In 1856 all counties were required to establish police forces and by 1862 all of England and Wales were being policed by regular paid police officers.

During the First World War the Special Constables Act of 1914 permitted the recruiting of Special Constables for the duration of the war. This worked so well that in 1923 another act of law was passed to allow for the continued recruitment of Special Constables – this being the founding of today’s Special Constabulary.

In 1964 the Police Act established the Special Constabulary in its present form giving Chief Constables the power to manage it.

Vigilante Groups

The action of the Justices was reinforced by voluntary self-protective measures on the part of the middle-class of town and county. In 1788, a rotatory system of nightwatching was introduced in Nottingham by which the citizens undertook to guard each other’s slumbers in turn.

During the1840s the Bingham Association for the Prosecution of Felons was in operation. Forty-two people attended the annual meeting in the King’s Arms (now the site of the Crown Inn) in 1848 and the Association offered a reward for information about sheep killing at Screveton in 1844. It would have been modelled on the Nottinghamshire Association for the Prosecution of Felons and Swindlers instituted in the year 1789. About the same time an association was organised in the County for the purpose of detecting crime, and bringing it the notice of the magistrates, who, it was said, welcomed any assistance to stem the rising tide of lawlessness.

More modern developments of self help might be Neighbourhood Watch and CCTV!