![]()

TEST PITS

ARCHAEOLOGICAL TEST PITS IN BINGHAM

THE ORIGIN OF BINGHAM VILLAGE

Elsewhere the history of the settlement of Bingham parish from the Mesolithic to the present is described. In this section the results from all the test pits are used to see what they tell us about the history of development of the village of Bingham.

EARLY HISTORY

The geological map shows lake deposits covering much of the northern half of

the parish. The lake existed for thousands of years, gradually silting up and

it is likely that by Roman times it was reduced to boggy land with no or little

open water.

While field walking Mesolithic flints were recovered from around the lake including parts of the lake that at the time had already been silted up. It seems that this may have been a place where the hunter-gatherers lived six to nine thousand years ago.

Part of the southern margin of the lake runs through the built-up area just south of the railway line. Several pits were dug along this marginal area. No microliths, such as would be characteristic of the Mesolithic period, were found, but in two of the pits (CB06 and CCLM10) there were cores, one of which was broken, from which microliths may have been taken.

Field walking showed that the first farmers came to Bingham about 6000 years ago and settled in the SW corner of the parish, near Lower Brackendale Farm. Over the next two to three thousand years their settlements spread along the stream that drains into the River Smite and which forms the southern border of the parish. By the early Bronze Age settlement had spread northwards towards the ridge line that runs just south of the A52. Very little indication was given in the field walking survey that settlement had crossed over the ridge line into the northern half of the parish and only eight pits yielded worked flints. There were no clearly identifiable tools among them, though two pieces looked like abandoned attempts to make scrapers. All the other fragments were flakes likely to be from late Neolithic to early Bronze Age periods. Though it is unlikely that a test pit would give good evidence of prehistoric habitation other than by accident, no information was acquired in this project to suggest that during this period there was any settlement in the area of modern Bingham before the Iron Age.

IRON AGE

At some time in the late Bronze Age or early Iron Age (c1500 to 700 BC) something

happened to cause a significant change in settlement pattern in the area. Iron

Age pottery is the oldest so far found in Bingham. During field

walking it was found in a number of small scatters mostly around the edge

of the parish. The three largest were in the northern half around Margidunum

and on Parson’s Hill and on the eastern limits of the parish near the

junction between Granby Lane and the A52. In the south there were four small

occurrences and all signs of the earlier, heavy influence of population in the

southern half had gone. What the event was that brought this about is not known,

but that time was a period of acute climate change and one of the largest eruptions

of the volcano Hekla in Iceland is known to have been in 950BC. This would have

had a major impact on the weather for several seasons, possibly leading to crop

failure , famine and death. Evidence of this eruption has been found in peat

deposits throughout the UK.

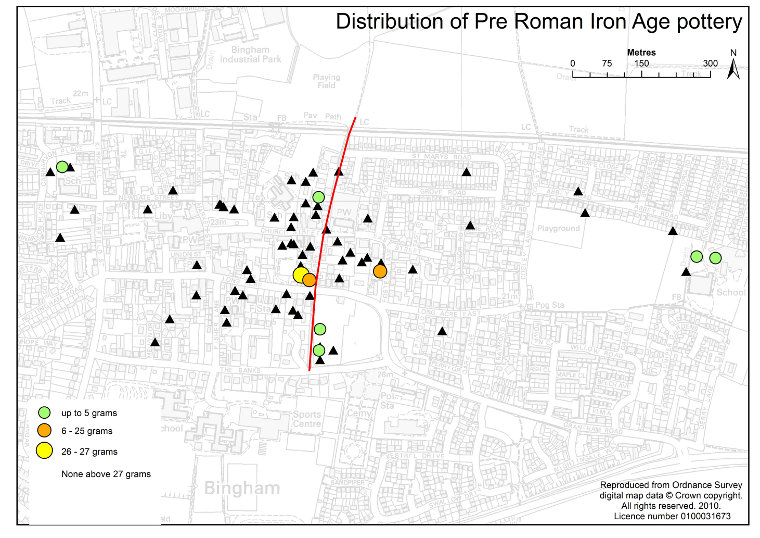

Fig 1 Map showing the location of pits containing Iron Age finds with a postulated track shown in red. Finds shown by weight in grams. Black triangles are pits with no sherds of this type.

Whatever the reason, the settlement pattern did change significantly and several pits showed Iron Age pottery in four discrete areas in the historic centre of Bingham to the south and the west of where the parish church now is. There is no running water near here and it is thought that the edge of the lake immediately to the north was marshland possibly with no standing water for some distance to the north. The question is why this site? Water would have been available from wells dug into the underlying Hollygate Sandstone and there is a possibility of springs along the boundary between the sandstone and the lake clay deposits, though none now exist. It is also possible that the Iron Age British were competent regarding the sinking of wells into sandstone. Whatever the method used to gain water at this site, there had to be a reason for them to choose it rather than go to a place with running surface water. One of very few possibilities is that this was a sacred site long before the Christians adopted it. The Iron Age British did have sacred sites at the edge of water or marshland in other parts of the country. Why not here?

Isolated occurrences of Iron Age or 1st century pottery were found in Carnarvon Primary School (CCLM03) and the Robert Miles Infant School (SHC02).

The quality of preservation of these sherds is generally poor and they provide no evidence of age. However, all except one of them were found in pits with Roman pottery and in two cases can be attributed to the first century. In the absence of any other evidence it is assumed that the Iron Age pottery in these pits may be late. In the parish as a whole there are some Scored Ware sherds picked up during field walking that could be attributed to the middle Iron Age, but not earlier.

The four main occurrences are two pits in Warner’s Paddock (LA20 and LA25), 2 pits in Cherry Street (LA09 and LA12), one pit in Church Lane (CB33) and one in Foster’s Lane (CB12).

The other occurrences are Carnarvon School (CCLM03, CCLM05) and a solitary sherd in Robert Miles Infants School (SHC02). Only this last one was not found in association with Roman pottery. In all the others the presence of Iron Age pottery seems to precede a long history of activity on the site.

ROMAN BINGHAM

Massive changes took place in the parish with the arrival of the Roman army

in

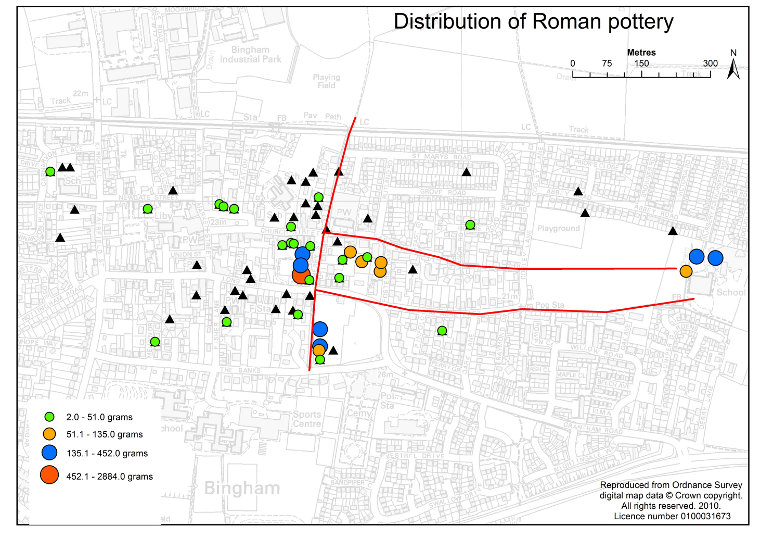

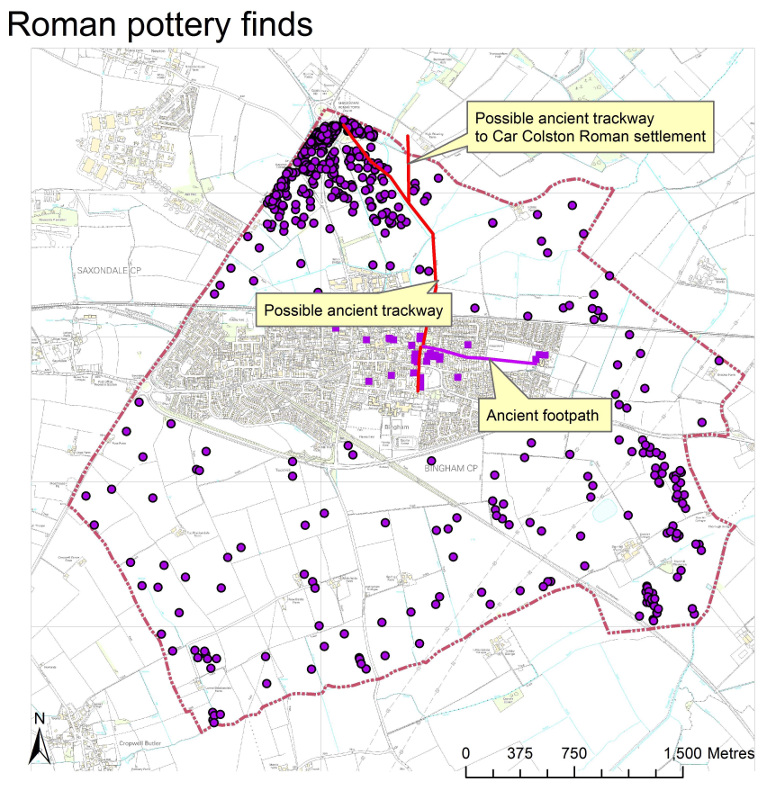

Fig 2 Map showing the distribution of Roman pottery sherds calculated by weight with postulated tracks in red. Black triangles are pits with no sherds of this type.

around AD53. The Fosse Way was built, or upgraded if there had been a pre-existing Iron Age road there; the small town of Margidunum was built and a villa was built on what is now the site of Carnarvon Primary School. There were also major changes in agricultural practice. The field walking gave indications of several clusters of Roman pottery scattered about the parish, in three cases in association with crop marks indicative of settlement, and about 70% of the fields in the parish yielded Roman pottery sherds. This seems to indicate the replacement of subsistence farming as practiced by the British before the Romans arrived by widespread commercial arable cultivation throughout nearly all the parish during the period of Roman occupation.

Roman pottery was recovered from 34 of the 73 test pits, but in only four clusters of pits was the quantity sufficient to consider that there may have been habitations nearby These were:

- Cherry Street where three of the four pits yielded a range of 33 to 212 sherds with an average of 99 per pit

- Carnarvon School where three pits yielded 17 to 68 sherds with an average of 38 per pit.

- Warner’s Paddock, where three of the six pits dug there and on the west of Jebb’s Lane yielded a range of 12 to 62 sherds, average 34 per pit.

- Foster’s Lane, where there were four pits yielding a range of 4 to 19 sherds, average 12 per pit

At all the other locations there were few Roman sherds and nowhere did they exceed 50 grams per pit, which has been judged empirically to separate manure scatter from possible domestic rubbish near a household. Most of these sites were west of the Jebb’s Lane – Church Lane line and east of Fairfield Street an area that was probably cultivated in Roman times.

Fig 3 Close-up of late Iron Age or 1st C sherd of Shelly Ware

(60617) in situ.

Fig 4 The late Iron Age or 1st C Shelly Ware sherd washed and cleaned.

A question mark hangs over the occurrences at Newgate Street and Holme Road largely because these two sites continue to yield sherds of all ages up to the medieval period. The sherds here may not be the result of manure scatter, but indicative of a small farm near by.

Cherry Street. The best evidence for habitation comes from Cherry Street. Four pits were dug in gardens that backed onto the land behind the Chesterfield Arms that was archaeologically investigated prior to the building of new flats there in 2005 (Raynor, T. 2006 Archaeological investigations on land to the rear of the Chesterfield Arms, 59-61 Long Acre, Bingham. Archaeological Project Services Report No 52/06) The pre-build investigations did not reveal any housing, but found evidence for a Roman field system established in the first century and used for arable cultivation and stock keeping. There is a suggestion of a decline in activity here in the second century with a revival in cattle husbandry and some industry in the third century. A cemetery was located here attributed to the later period of activity. Raynor did speculate that the field system might have been worked from the villa in Carnarvon School.

All the pits in Cherry Street yielded Roman pottery and in one of them, LA09, there was good evidence for a habitation nearby. The content of this pit suggests that it was dug into a domestic Roman rubbish dump. There was a wide range of pottery types from grey ware to samian ware with plentiful bone at the level of Roman pottery, thin pieces of Roman brick and some roofing material which has been identified as a Liassic limestone found locally in Barnstone. This fossiliferous limestone was used on high-status medieval buildings in Bingham such as the medieval manor house (CB01) and the medieval rectory (CB02), but this is the first time it has been recorded at a Roman site. Regency House (LA12) to the south of LA 09 and in a pit only around 20 metres from it, yielded only one Roman sherd, but to the north along Cherry Street two other houses (CB17, CB21) provided rich assemblages.

Carnarvon Primary School has long been known as a place where there was a Roman villa (Gregory, A. 1969 A Romano-British site in Bingham. Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire, 73,105-110.). Reference to it has been made on the BHTA website and some of the pottery found there has been re-identified and photographed. One of the pits (CCLM03) yielded the best fragment of a late Iron Age or first century pot found in any pit in this project. It was nearly half a complete pot. Most finds came from pit CCLM05. As with CCLM03 a sherd of Iron Age ware was found here. The Roman pots, however, were numerous and included grey ware, Nene Valley Colour-coated Ware, Fine Orange Ware, shell-tempered ware types and White Ware mortaria. One large part of a mortarium was lying inverted on a stone that showed signs of having been used for rubbing. While most of the sherds were grey ware such as would be used in the kitchen there was a fragment of a higher status Hunt cup. The date range is 1st to late 4th C, which confirms the long time range identified in the earlier assemblages that were collected from here. In the whole of Bingham only here, Margidunum and the double-ditch enclosure near Starnhill Farm yielded finds from the late 4th C.

Warner’s Paddock. Five pits were dug in the field and one in a garden on the other side of Jebb’s Lane. Of these, three had a fairly high content of Roman pottery. These were LA21, LA24 and LA25, which form a linear group along the edge of Jebb’s Lane. Two of them seem to be on slightly raised platforms. The significance of the platforms is not known because these pits also yielded a strong

Fig 5 Jebb’s Lane, a sunken lane alongside Warner’s Paddock, up to 3 m below the level of the adjacent field in places.

assemblage of Late Saxon pottery. LA 21 yielded the most Roman material. 77% of it was grey ware and difficult to date, but among the remainder were sherds of samian ware, Nene Valley colour-coated ware, white mortaria, Medium Sandy Oxidised Ware and shell-tempered wares. The date range is from 1st to early 4th C. In terms of quantity, there are indications of the possibility of a household nearby. Certainly, there are plenty of bones and teeth with the Roman pottery in this pit including a boar tusk. A piece of red clay roof tile was also found at this depth.

Foster’s Lane. All four of the pits dug here, CB12, CB13, CB23 and CB24, yielded Roman pottery, but in none of the pits was it abundant. The most recovered was 19 sherds from CB23. However, at Carnarvon Primary School where it is known that there is a Roman villa as few as 17 sherds were recovered from one of the pits. In test pitting abundance itself in a single pit is not that significant. In the Rectory pit (CB11), which is some 25 metres from CB23 there were 8 sherds. This is the most from any pit outside the four clusters considered here and it indicates that there is an area including these five pits with higher than

Fig 6 Roman pottery in the whole parish. The main cluster in the north is around Margidunum. Some of the other small clusters are coincident with crop marks indicative of settlement and seem to suggest there were small farms in much of the southern part of the parish. The red line is a postulated track leading from the southern limit of the settlement in central Bingham along Jebb’s Lane, Cherry Street and church Lane across the fields to Parson’s Hill and thence to Margidunum. The east-west track from near the church leads to the villa at Carnarvon School. There is a possibility of a western extension from the church.

average abundances, which may indicate that there was a Roman homestead nearby. There are several interesting aspects to this pattern of distribution of Roman sherds.

Firstly, in each of the four clusters there is Iron Age pottery, probably indicating that except for Carnarvon School where the villa was built the inhabitants were British who had become influenced by the Romans.

Secondly, the three clusters in central Bingham are close together. In the southern half of the parish the isolated clusters considered to be indicative of small farms sites out in the fields are all more than 800 metres apart. This suggests that there is a difference in significance between these clusters and the ones identified in the pits in central Bingham.

Thirdly, the three central Bingham clusters are either side of a line through Jebb’s Lane and Cherry Street. Jebb’s Lane is a sunken footpath as much as 3 metres below the adjoining field, which could indicate great antiquity. It may be significant that Iron Age and Roman pottery, albeit in small quantity, was also found in pits along Church Lane (CB15, CB33), which is a further extension of this line. If taken northwards Church Lane passes into a footpath across the railway line that leads to Iron Age and Roman settlements indicated by artefacts found during field walking and crop marks on Parson’s Hill that are visible on air photographs. The crop marks (See Bingham Back in Time) show various structures interpreted as housing and it is noticeable that the Iron Age and Roman pottery scatters here are side by side as though the settlement site moved to the east under Roman influence. It is postulated that this route, from The Banks down Jebb’s Lane, via Cherry Street and Church Lane to Parson’s Hill has been used since the Iron Age and that as early as the Iron Age the clusters of settlements in central Bingham were strung along it.

Two other tracks are postulated (see Fig 2). One leads eastwards from where the modern church is and leads to Carnarvon Primary School villa. The other, to the south, starts from near the test pit at the southern end of Cherry Street that yielded 2.8 kg of pottery and also goes to the villa.

ANGLO-SAXON BINGHAM

When the Anglo-Saxons came to England at the end of the Roman period they mostly

lived in small, scattered settlements. In Bingham, field walking showed these

to be in three centres around the boundary of the parish, all sites that had

been occupied by the Romano-British and the Iron Age British before them. They

did not use a lot of pottery in their daily life and finds of Anglo-Saxon sherds

are never common. Moreover, unless they have some form of decoration they are

difficult to date. Mostly, the sherds found can only be described as spanning

the early to middle periods; that is 450-850 and are treated as one period.

However, among these there are some definitely Early Anglo-Saxon(450-650) and

two definitely Middle Anglo-Saxon.

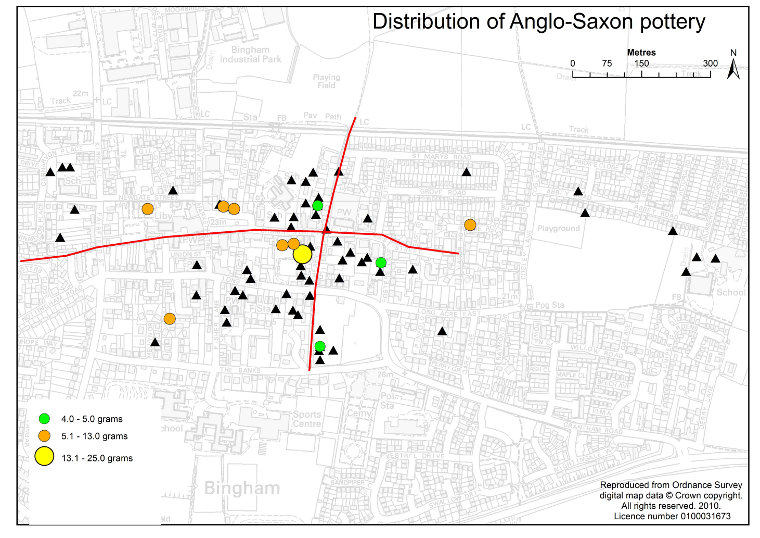

Fig 7 The distribution of early/middle Anglo-Saxon pottery plotted by weight in grams. Red lines are postulated tracks. Black triangles are pits with no finds of this type.

Only eleven of the test pits yielded Anglo-Saxon pottery sherds. These include single pits in the clusters on Warner’s Paddock (LA24), Cherry Street (CB21) and Foster’s Lane (CB13), where there is evidence of activity, possibly habitation, since the Iron Age. Of these three sites pit CB21 yielded three sherds of Early Anglo-Saxon Local ware (450-800). They were three different fabrics and were the most recovered from one pit. The two from Warner’s Paddock were Charnwood Ware and likely to be from the same vessel. The sherd from Foster’s Lane was sandstone tempered and dated 550-800, a somewhat later start date than the others.

Though the quantity of Iron Age and Roman sherds from the Church Lane pits is very small there is continuity here and CB15 yielded a hand-made sandstone tempered sherd, which could be identified as Carboniferous sandstone. This has a date range 450-800.

Besides these, an Early Anglo-Saxon Local Ware sherd was recovered from Holme Road (CC03). In LA19 at The Paddock the only example of Central Lincolnshire Early to Mid Saxon sandstone-tempered pottery (450-750) found in Bingham was recovered. Two sherds of Charnwood Ware and Early Anglo-Saxon Local Ware were taken from CB25 in Newgate Street, while both pits on the north side of Market Place (CB34 and CB35) contained Anglo-Saxon pottery. In CB35 there were two sherds of Early to Mid Saxon Sandstone-tempered Ware with the temper being identifiable as Carboniferous sandstone (450-750). CB34 is one of two occurrences of Middle Anglo-Saxon sherds in Bingham. It is a Mid Saxon non-local fabric with a date range 650-870. The other is pit CB37 behind the Chesterfield Arms where a sherd of Middle Anglo-Saxon Maxey-type Shelly Ware was recovered.

Fig 8 Pits containing Late Saxon sherds, plotted by weight in grams. Red lines are postulated tracks. Black triangles are pits with no finds of this type.

Though small in quantity there is some diversity of type here and judging by the material used as a temper some of it was not made locally. Pottery with both the Charnwood and Carboniferous temper would have been imported from areas to the west.

The sites of the test pits are well spread out, but the distribution of the finds is similar to that seen in the scatters found field walking and it is safe to postulate that the Bingham cluster was a small settlement area, one of four with Anglo-Saxon pottery within the parish, all of which were occupied from the Iron Age. Sherds of both Early and Middle Anglo-Saxon age were found showing that there was occupation here throughout the whole of the period 450 to 850.

The significant difference between the Anglo-Saxon distribution and anything earlier is that the distribution of the sherds shows that it is possible there was habitation west of the church around the Market Place area. It is postulated that there was a track linking the Market Place area to the church, but that the track from the church towards the Roman villa at Carnarvon Primary School had lost its significance as there was no suggestion of an Anglo-Saxon presence there.

BECOMING A VILLAGE

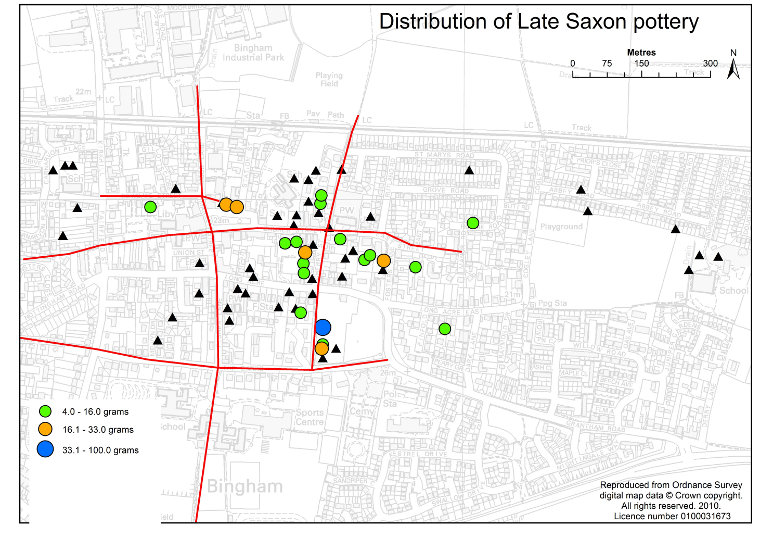

In marked contrast to the Early/Middle Anglo-Saxon period pottery was widely

used in Late Saxon times. 89 sherds were recovered from 21 pits. The commonest

type was Torksey Ware and Torksey-type Ware. Others fabric types include Lincoln

kiln-type Shelly Ware, Lincoln Shelly Ware, Late Saxon Local Fabrics, Stamford

Ware A, Early Stamford Ware Fabric A, Shell-tempered non-local Late Saxon Fabrics

and Lincoln Sandy Ware. The Torksey Ware falls within the date range 870-1050,

with most of the others falling within the range 875-1000. This makes it very

useful in that manufacture ended as the Norman Conquest began. Some of the sherds

showed decoration of various types and an Early Stamford Ware sherd had a yellow

glaze. As with the earlier fabrics the temper varied and one sherd had a distinctive

red sandstone temper, probably the Triassic Sherwood Sandstone. The nearest

outcrop of this rock is in Radcliffe on Trent. Where the forms could be identified

there were cooking vessels and a spouted pitcher.

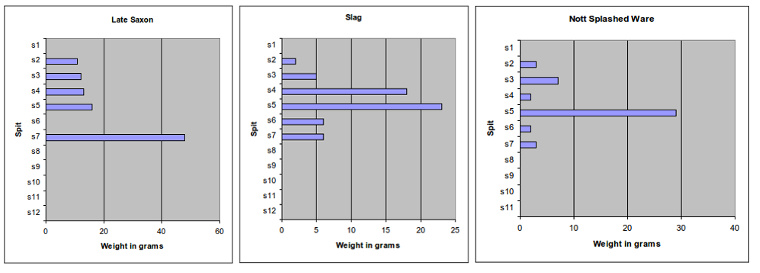

Fig 9 Three plots for pit LA21 in which the maximum abundance is shown with depth for three types of find. They show that the maximum for slag coincides with the maximum for Nottingham Splashed Ware, one spit higher than Late Saxon

During field walking only around 50 finds for the whole Saxo-Norman period (870-1250) were collected and they were not differentiated into Late Saxon and post Conquest. The sharp difference in the pattern of distribution in the parish as a whole between the Early/Middle Anglo-Saxon and the Saxo-Norman periods showed that around the end of the Middle Saxon period there was a significant change in where people lived in the parish of Bingham. Except for near Margidunum all signs of the dispersed settlements that had characterised earlier periods had gone and the broad scatter of Saxo-Norman pottery showed that widespread, possibly commercial agriculture had returned. It is speculated that this may have coincided with the introduction of open-field farming. In a process called village nucleation the people moved from dispersed, self-sufficient settlements in the countryside into settlements concentrated around the church to form England’s first villages (Williamson, T. 2003 Shaping Medieval Landscapes, Society, Environments. Macclesfield). Elsewhere in the East Midlands this process took place from the 8th century onwards. In Bingham the change in the pattern of distribution of finds between the Early/Middle Anglo-Saxon and Late Anglo-Saxon suggests that it might have been in the 9th century here. It is interesting that the only two confirmed sherds of Middle Anglo-Saxon pottery were found west of the church. Some of the Early/Middle Anglo-Saxon finds from this area cannot be so closely dated and may well also be Middle Anglo-Saxon. This raises the possibility that when the people from the dispersed settlements migrated to Bingham they chose to settle in the area west of the church, thus expanding the village westwards. This migration could have happened at any time in the Middle Anglo-Saxon period (670-850).

There is a reference to the village of Bingham in the Domesday Book, but its location is not known. The likelihood is that it was where Bingham is now. There are indications that pottery was used more during the Late Saxon period (850-1050) than earlier and the distribution is more widespread. There were moderately high concentrations in the pits at Warner’s Paddock, Cherry Street, Foster’s Lane and Market Place, in other words in the core of the Bingham settlement as it had been since the Iron Age. It is also notable that the highest concentrations are in Warner’s Paddock. In one pit (LA21) there were 26 sherds. In addition, this pit yielded plentiful pieces of fuel-ash slag. One piece from this pit was attached to a sherd of Stamford Ware Fabric A. This fabric type has a date range 1000-1150. Another piece of slag from LA25, the adjacent pit, was found resting on a sherd of Torksey-type Ware. There were several different types of slag, all typical of smithy slag and it suggests that there was a smithy hereabouts at least during the 11th C. However, in LA21 the slag was found at all depths from 10 to 70 cm, with the maximum between 40 and 50 cm. This coincides with the maximum for 12th C Nottingham Splashed Ware. The maximum for Late Saxon finds was below this at 60 to 70 cm. There is no doubt that the attachment of the fuel-ash slag to the Stamford Ware A sherd indicates that there was a smithy here in the 11th C, but the overall distribution of slag seems to suggest that this activity continued hereabouts at least to the 13th C. Whether it was a permanent feature or a place where a peripatetic smith visited from time to time is not known. This interpretation of the contents of the pits here certainly enhances the importance of the settlement in Warner’s Paddock during the period immediately before and after the Norman Conquest.

While the presence of Late Saxon sherds in Foster’s Lane and Cherry Street show how these sites continued to develop from the Iron Age, the appearance of sherds of this age in the two of the Market Place pits and two of the pits behind the Chesterfield Arms is significant in a different way. All four of these pits (CB34, CB35, CB05 and CB37) also produced Early/Middle Anglo-Saxon pottery, while two of them had Middle Anglo-Saxon sherds. If this area is the part of Bingham that came to be settled first at the time of village nucleation in the Middle Anglo-Saxon period, as suggested earlier, it continued to grow in importance before the arrival of the Normans.

Low concentrations of Late Saxon finds were found in several other pits, among which are Holme Road (CC03) and 9 Newgate Street (CB25), both of which had yielded Roman and Early/Middle Anglo-Saxon sherds. The pit in Long Acre LA14 produced a single Late Anglo-Saxon sherd, which is the start of the archaeological record here. It is difficult to be sure how to interpret these, but it seems to show that the idea that the village of Bingham grew around a cross roads centred on the church. The west-east road extended from the church towards 9 Newgate Street; the eastern extension went to near Holme Road.

During the early/middle Anglo-Saxon period, while the population lived in dispersed settlements and practiced a form of agriculture based on local self-sufficiency, sherd scatters can be interpreted as indicative of settlement with reasonable confidence. After village nucleation and the change in agricultural practice this may not be true, because broken pots could find their way into the fields with farmyard manure. In the case of Holme Road and 9 Newgate Street there is a continuity from earlier periods that suggests that these may still be settlement sites, but LA14 may well be from manure scatter.

If open field farming did start in the Late Saxon period then the road now called The Banks may well have come into existence then to provide access to the open fields, three of which lay to the south of The Banks. It is a hollow way and clearly of some antiquity. In view of the later development of the medieval manor house site to the northwest of the Market Place it is thought that there would have been tracks to the open fields from here to the south following Market Street and Fisher Lane and to the west along Newgate Street and School Lane.

POST NORMAN CONQUEST

Saxo-Norman pottery is so called because some of the identifiable fabrics, which

fall with the date range 870-1250, span the Norman Conquest. Most pottery found

here is Stamford Ware and several different fabric types have been identified

and given date ranges. These start with fabric A that is usually pre-Conquest

but may overlap 1066. Some of the other Stamford Ware fabrics continue until

around 1250.

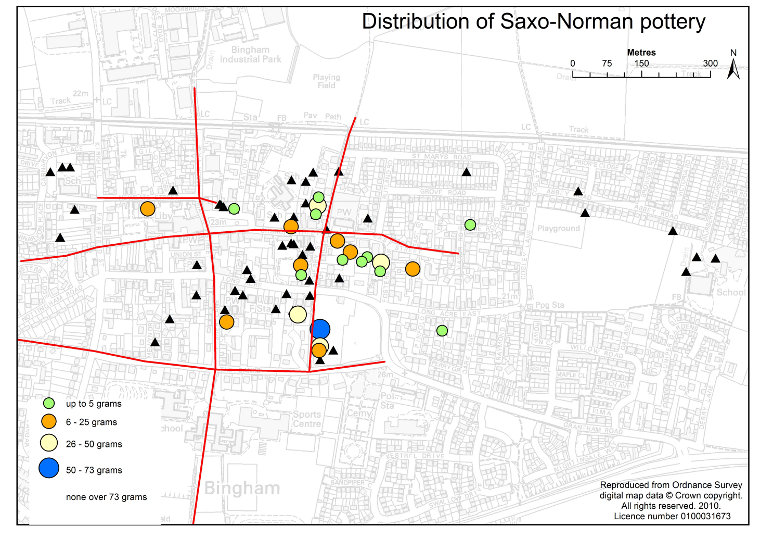

Fig 10 The distribution of Saxo-Norman pottery. This shows the continuing spread of the village in the period after the Norman Conquest. By this period there was possibly a road south from the Market Place. Red lines are postulated tracks. Black triangles are pits with no finds of this type.

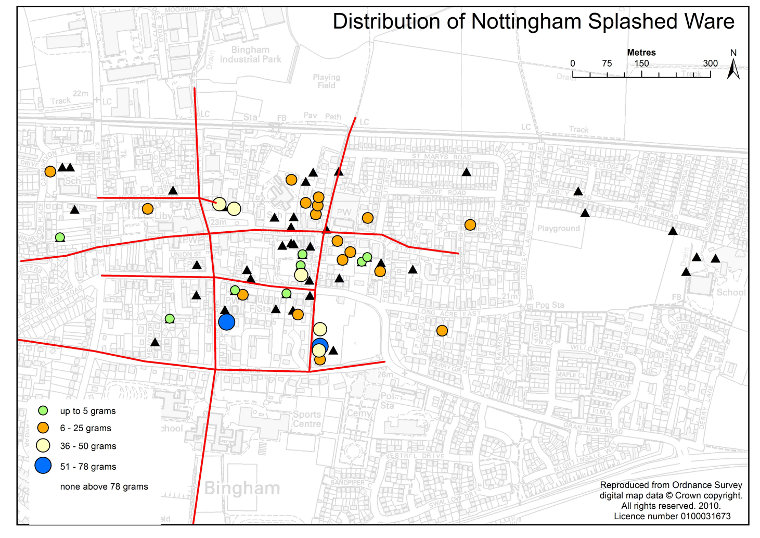

Fig 11 Pits with Nottingham Splashed Ware. Red lines are postulated tracks. Black triangles are pits with no finds of this type.

Pottery of this age range was found in 25 pits, in 65% of which there were only one or two sherds. However, the pits in Foster’s Lane, Church Lane, Cherry Street and Warner’s Paddock yielded sufficient Saxo-Norman pottery to indicate the continued growth of village Bingham immediately after 1066. Saxo-Norman pottery also appears in some pits that did not have Late Saxon or earlier sherds, though in quantities that suggests it may have got there in a manure scatter.

Nottingham Splashed Ware with a range through the 12th into the mid 13th centuries came in about a century after the Norman Conquest. It is the first pottery to be made in quantity in Nottingham. From the appearance of the first product in 1100 the fabric types changed over time, probably as a result of improved manufacturing techniques, and there are several types of splashed ware with different characteristics that can be dated. Some varieties can be tied down tightly to, say, 1125-1175 and 1140-1180. The importance of Nottingham Splashed Ware for the purposes of the story of Bingham is that it was more widely used that any previous fabric type. 33 out of the 56 pits in which medieval pottery was recorded contained it and it was the dominant fabric type in several pits. It is plentiful in pits on Foster’s Lane, Warner’s Paddock, Cherry Street and Church Lane. This is the ancient core to Bingham, but there are indications of a strengthening of the community in the area west of the church. Two of the Market Place pits have a high content of Nottingham Splashed Ware sherds. One of these is on the site of the medieval manor house. The lords of the manor who owned the parish were not residents in Bingham until the middle of the 13th century, but the quantity of splashed ware found here suggests that this may have been where his steward lived before then. The fact that the manor house was built here does, however, raise the status of this part of Bingham and make it the focus for the development of the village after the mid 13th century.

The appearance of Stamford Ware alongside Nottingham Splashed Ware in Fisher Lane is the first indication of any kind of activity in this street. The two Stamford Ware finds here (LA11) are Stamford Ware B and B/C, which fall in the date range mid to late 12th to early 13th C, a century or so after the Norman Conquest. Like Jebb’s Lane Fisher Lane is a sunken lane and it is possible that this route was used for access to the fields that were south of where the A52 now is from habitations around the Market Place. On maps from the 16th to 18th centuries this is shown as a road to Wiverton.

Three of the pits along Long Acre contained Nottingham Splashed Ware. This suggests the possibility of the existence of a track along this route in the 12th century.

PROSPEROUS BINGHAM

Field walking showed more pottery scattered over a wider area from the 13th

and first half of the 14th centuries than at any time before or since until

the 19th C. It is evident that nearly all the parish was either under cultivation

or was used for grazing. This was not a sudden change in fortune, but a gradual

trend possibly starting back in the 9th century and possibly reflecting on a

gradual increase in population, but it also coincided with the time that the

lords of the manor lived in Bingham. At such a time various tradesmen and craftsmen

would have been attracted to live in the village contributing to an increasing

level of prosperity.

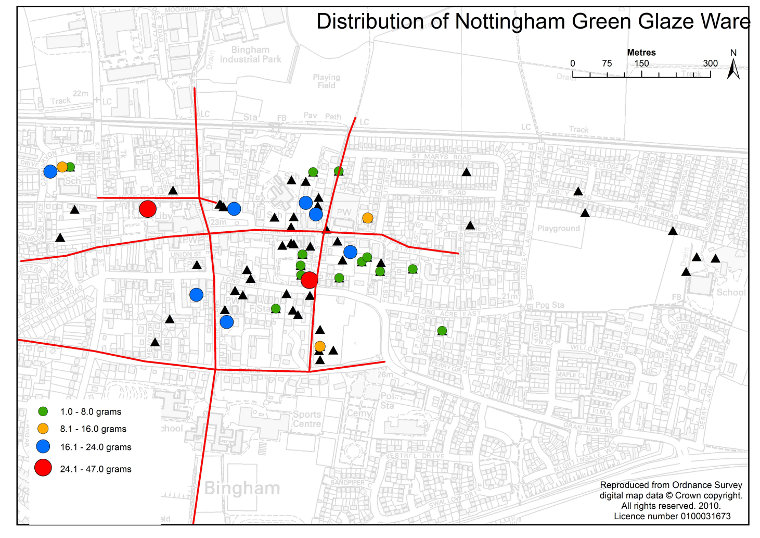

Fig 12 The distribution on Nottingham Green Glaze, a pottery type generally with dates within the range1250 to 1350. Red lines are postulated tracks. Black triangles are pits with no finds of this type.

In the mid 13th C Nottingham Splashed Ware gave way to Nottingham Green Glazed

Ware and Nottingham Light-bodied Green Glaze Ware, but there are, in fact, many

fabric types for this period and later. Overall, 39 different medieval fabric

types were described from the test pits, among which 52% were made in Nottingham.

Dominant among these are Nottingham Reduced Green Glaze, Nottingham Green Glaze,

Nottingham Light-bodied Green Glaze and Nottingham Coarse orange/pink Sandy

wares. Around 42 pits yielded one or more of these types, with other pits presenting

more uncommon fabric types from the same period. From the abundances in the

test pits it can be shown that after 1250 Bingham contracted in the area of

Warner’s Paddock, but continued to expand west of the church.

The most significant impact on life in Bingham was the arrival of a resident

lord of the manor for the first time in its history. Ralph Bugge acquired the

manor in 1266 and settled it on his son Richard, who later became Sir Richard

de Bingham. His son, William, succeeded him, but died in the Black Death. It

was William and his widowed mother Lady Alice who persuaded King Edward II to

grant Bingham a market charter in 1314. The manor passed to the Rempstone family

from the de Binghams. There is no documentary evidence to say where they lived.

The first of them, Sir Thomas Rempstone (died 1406) was handsomely rewarded

for his services to king and country in the wars in France, but his son, also

Sir Thomas (died 1458) suffered financially as a result of being captured and

held to ransom by the French in 1429 and 1442. However, Margaret, the widow

of the senior Sir Thomas lived until 1454 and controlled most of the family

property. It is very likely that she lived in Bingham. Both she and her husband

are buried here. We do have documentary evidence that the manor house was derelict

in 1586.

The pits dug over the site of the old manor house (CB01, CB01E and CB34) yielded the most medieval pottery finds from all pits and also showed the greatest diversity. Also this is the only place in Bingham to have Saintonge Ware. This type of pottery was made in a village near Bordeaux and was exported with wine from there to England throughout the medieval period, but it was particularly common in the 13th C.

There are several important factors in the distribution of finds for this period:

For the first time since the late Roman period there are finds at Carnarvon Primary School sites. Excavations there carried out during recent building phases have also revealed a medieval presence.

The highest proportion of medieval finds in any pit in the town came from the old manor house pits on Market Place. This supports the other indications that the manor house was now the focal point for Bingham.

The Church Lane, Cherry Street and Foster’s Lane sites all lose their individuality amidst the spread of medieval finds.

At Warner’s Paddock, however, after yielding one of the highest counts of Nottingham Splashed Ware, there is hardly any medieval green glaze for the period after 1250. It seems that the arrival of the lord of the manor to live near the Market Place brought about a switch in the centre of Bingham from Warner’s Paddock to Market Place.

For the first time pottery sherds have been recovered from pits to the east and substantially north of the church.

The sites at Holme Road and Newgate Street were still yielding pottery sherds.

THE OLD MANOR HOUSE

There is one known reference to the lord’s manor house and that was in

the manorial survey of 1596 when a reference was made to the old manor house

on the north west side of market place being in a state of ruin.

Three pits were dug in the area where it is thought the manor house might have

been, ((CB01, CB01E and

CB34) and they all yielded

evidence of it. A fourth pit, CB35,

was dug close by but east of the suspected limits of the manor house.

In CB01 and CB01E a stone feature was encountered at around 80 cm depth which

is thought to be the remains of a stone foundation layer possibly to a medieval

tiled floor. The stones were set on a layer of red-brown clay, which was also

used as a filler between the stones. Its maximum thickness was 8 inches, though

most of it has been robbed. Some small pieces of 3 cm-thick glazed, medieval

floor tile were found on it.

All the pottery found beneath the floor has a date range up to early 14th C with Nottingham Splashed Ware the most common. This suggests that the floor could have been laid in the late 13th C.

Evidence that the occupant of the house was a rich man is in the presence of objects such as oyster and whelk shells, butchered beef, sheep, pig and venison bones, painted wall plaster, smoke-stained brick pieces, large lumps of coal and Saintonge pottery beneath the floor and a silver penny from the early 14th C above it.

Fig 13 Pit CB34 showing the degraded remains of the gypsum plaster and lime floor. The grey part in bottom right is where the floor was lifted and then backfilled. The stone wall is top right.

Fig 14 Silver penny minted in the reign of King Edward I, probably after 1290.

Between 10 and 20 cm above the floor is a layer consisting mainly of limestone roofing tiles, many of which have 1/4 inch holes drilled through them. Rusting iron nails are embedded in some of the holes. The limestone has been identified as coming from a quarry in Barnstone that is still being worked for lime and in the 19th C supplied paving. This layer has been interpreted as the result of a roof collapse. All the pottery found between the stone floor and the layer of roof tiles falls within a date range 1350-1450. The pottery above the layer of roof tiles is dominated by Midland Purple Ware (1380-1600), which is not found beneath it. The sequence of pottery types from beneath the stone floor to above the layer of tiles shows that the place did not become uninhabited after the Black Death. Instead it shows that the deterioration of the house and collapse of the roof was likely to have been after about 1400. This chronology broadly agrees with the documentary evidence of occupation from 1266 to around 1440.

Fig 15 Limestone roofing tile, probably quarried at Barnstone. It is a Liassic limestone, identified by characteristic fossils and was quarried here for paving stones in the 19th C.

Fig 16 The plaster and lime floor. From bottom right to upper left: clay, sand, flat stones, lower plaster and lime layer, upper layer.

Fig 17 Gypsum plaster showing indentations where it had been pushed against a stone wall

Fig 18 Stone wall 20 inches wide made of local sandstone and sandy mortar.

The importance of this interpretation of the sequence revealed in the north wall of pit CB01 is that it defines the period during which the manor house would have been occupied. In the pit next door, CB34, another floor was found, but in this case, although the pottery found below it is the same as below the stone floor feature in CB01, there is not such a tight definition of final occupancy. The floor in this pit is gypsum plaster and lime and it is set to within a few cm of the front wall of the house. This wall is 20 inches thick and well made using local sandstone set with sandy mortar. The floor behind it is badly degraded in parts and is covered with rubbish among which are limestone roofing tiles, white gypsum mortar used as a finish on a stone wall, fragments of dressed building stone and pottery. The most significant pottery consists of several large pieces of a Midland Yellow Ware pancheon (late 16th to 17th C) that makes up about 40% of a whole pot. One or two pieces of medieval pottery were recovered among the rubbish, but they are not as reliable an indicator of the upper age limit for the use of the floor as in CB01. The fact that the rubbish is laid on a degraded floor and that the reference to the derelict building is in 1586 suggests that the rubbish came long after the building was last in use.

There are few references in the literature to the floors of medieval buildings and we have not yet managed to trace any reference to plaster and lime floors before the Tudor period. The dating of the floor in CB01 suggests it had to have been laid between 1266 and 1450 at the outside. The fact that Sir Thomas Rempstone jnr was ransomed by the French put the family under severe financial strain, making it unlikely that expensive building work would have been carried out after about 1430. There is a record in Salzman’s book on English castles (Buildings in England down to 1540, Oxford University press, 1952) dated to 1252 of King Henry III demanding that the rooms in Nottingham castle be “finished” with plaster of Paris (gypsum plaster). There is a plentiful supply of both gypsum and limestone in the region. While gypsum plaster sets very quickly lime cement sets slowly. Mixing the two to get a setting time that enables the surface to be worked flat without a rush seems to be sensible.

Both of the floors excavated in the three pits are well laid. In CB01 and CB01E about eight inches of stonework set on red-brown clay underlie the tiled surface. In CB34 there are five layers to the plaster and lime floor. A layer of sand had been put on the clay soil. Flat stones had been set in the sand and then a layer of plaster and lime laid on that. This is very crumbly and seems to have been a failed attempt at a floor. It was then covered with a skim of white plaster probably to seal it and the upper plaster and lime layer put down. This one is about 4.5 cm thick and set hard. The gypsum plaster and lime mix is in a ratio of about 4 to 1. This sequence suggests experimentation. [Full details of the gypsum plaster and lime floor can be found in Allen and Cooper (2016) ‘The use of gypsum plaster and lime-ash for flooring in medieval East Midlands: Evidence from Bingham Nottinghamshire’ TTS Vol. 120, 55-69, 2016.]

Tiled and plaster and lime floors and limestone tiled roofs would have been expensive and it is unlikely that anyone other than a lord of the manor could have afforded them. Accepting that the Rempsones did live here, there are four of them and at least three of them fought for King and country in Wales, Scotland and France. They had the potential to add income from ransoms and looting to the income from rents and could well have been rich enough to pay for this sort of expense on the house. In addition, Bingham’s stone-built parish church, which was started in 1220 was finished during the late 13th C, possibly funded by Sir Richard. The wealth of the finds beneath the stone floor in CB01 suggests that both of the floors we located were additions to the earlier structure, probably put in around 1300. With the roof collapse in the mid 15th century this presents a date range for this unusual plaster and lime floor of 1300-1450.

IMPACT OF THE BLACK DEATH

The first outbreak of the Black Death came to England in 1348/49 and though

none of the later ones were as widespread as the first outbreak, nor as devastating,

there were another five visitations in the second half of the 14th C. These

were 1361-64, 1368, 1371, 1373-75 and 1390. Whether any of the later ones was

felt in Bingham is not known, but the 1390 outbreak is recorded elsewhere in

Nottinghamshire.

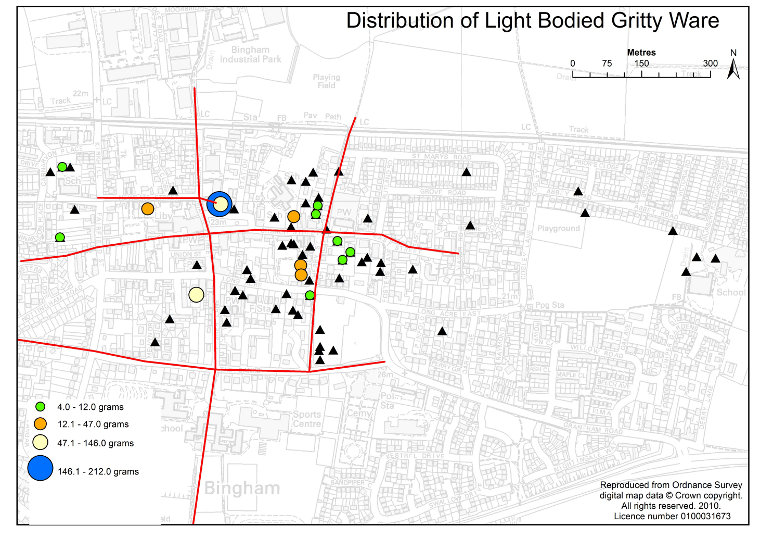

It is difficult to find a way of measuring the impact of the Black Death in the absence of documentary evidence, but an approximate estimate can be found by studying four common and well dated fabric types.

There are two common fabric types that are found predominantly within the 13th C. These are Nottingham Green Glazed Ware, which has a range generally 1270-1350 and Nottingham Light-bodied Green Glazed Ware, which also has a predominant date range ending before 1350. Only four of the light-bodied finds recorded extended beyond this date. In three of them there were younger fabrics in the assemblage, so it did not matter. The other one, with a range 1375-1400, was a solitary find in the pit and has been recorded in the table in the Light-bodied Gritty Ware column.

Nottingham Reduced Green Glaze is more difficult. About half of the finds have a date range of 1300 to 1400 or 1450. Of the rest about 32% of the total have a range with a post-1350 start, while 14% have a date range that ends prior to 1350.

The fourth is Light-bodied Gritty Ware, which is invariably dated after the Black Death with varieties dated 1350-1450 or later and some dated 1375 onwards.

In the Market Place pits there was no record of any Nottingham Green Glazed

Ware, though Nottingham Light-bodied Green Glazed Ware was abundant. In this

and seven other areas (see Table 1) the full range from Nottingham Green Glazed

Ware to Light-bodied Gritty Ware was represented. Here it is possible to conclude

that there were sufficient survivors of the

TABLE 1

| Pit Area | Pit Numbers | NGGW | NLBGGW | NRGGW | LBGW |

| Market Place | CB01, 01E,01A, CB34,35 | X | X | X | |

| Church Lane |

CB14,15,19,33 | X | X | X | X |

| Cherry St |

CB06,17,21,LA09,12 | X | X | X | X |

| Rectory |

CB07, 11, 20 | X | X | X | X |

| Bingham Infants |

SHC01, 02, 03 | X | X | X | X |

| Church St |

CB22, 27 | X | X | X | X |

| Newgate St |

CB25 | X | X | X | X |

| 24, Long Acre |

LA07 | X | X | ||

| Warner’s Paddock |

LA06,15, 24, | X | X | X | |

| Robt Miles Jun |

CB02, 04 | X | X | ||

| Carnarvon Sch |

CCLM04, 05 | X | X | ||

| Fisher La |

LA11 | X | X | ||

| Foster’s La |

CB12,23,24 | X | X | ||

| Long Acre East |

LA14 | X | X | ||

| 50, Long Acre |

LA04 | X | |||

| 79, Long Acre |

LA13 | X | |||

| 8 East St |

CB32 | X | |||

| Rutland Rd |

CB31 | X | |||

| The Paddock |

LA19 | X1 | |||

| 10, Newgate |

CB26 | X2 | |||

| Fairfield St |

SHC05 | X |

NGGW Nottingham Green Glazed Ware

NLBGGW Nottingham light-bodied Green Glazed Ware

NRGGW Nottingham Reduced Green Glazed Ware

LBGW Light-bodied Gritty Ware

X1 All the other medieval sherds associated with this are pre-1350

X2 This is NLBGGW with a date range of 1375-1400

plague for life to continue at their home site throughout the epidemic.

In three sites, Carnarvon Primary School, Robert Miles Junior School and Warner’s Paddock, there were pre-1350 finds and Nottingham Reduced Green Glazed Ware, which has a general date attribution of the 14th C, but no Light-bodied Gritty Ware. Without being able to say whether the Nottingham Reduced Green Glaze Ware found was made and broken before or after 1350 it cannot be said that there was no activity here after the Black Death. Instead it is safest to postulate that there was a slow decline, possibly a result of the later outbreaks, eventually leading to the settlement areas dying out some time in the second half of the 14th C.

In eight other areas there are no sherds with date ranges that post-date the

mid 14th C. Another pit ((LA19)

yielded only Nottingham Reduced Green Glazed Ware among the four markers used

here, but it was found in an assemblage of less common types that was entirely

pre-Black Death. It is probably safe to assume that in all seven of these the

settlements or farms died out with the Black Death.

In four pits (CB26, SHC05,

LA26, LA33)

there is nothing earlier than Light-bodied Gritty Ware among the markers used

here. CB26 does contain Nottingham

Coarse pink/orange Ware with a date range 1250-1350, but the whole deposit in

this pit is highly disturbed and little significance can be attributed to the

medieval material. Pit SHC05, dug at the margin of a 19th rubbish pit, yielded

only four medieval finds, one of which was Light-bodied Gritty Ware. The others

cover the time range 12th –15th C.

Test pitting offers no reliable way to calculate what the population decline may have been. In terms of the number of pits areas with pre-Black Death finds in them that had nothing after the mid 14th C the decline would be 42%. Counted on the basis of individual pits it is 23%. Calculated in terms of the reduction in the weight of light Bodied Gritty Ware (620gm) compared with two common pre-1350 ware types Nottingham Green Glaze and Nottingham Light-bodied Green Glaze (800) there is a drop of 22.5%. None of these can be regarded as definitive, but they suggest that losses were around a quarter of the population, which is within the range normally stated nationally.

Fig 19 Pits containing Light-bodied Gritty Ware. Note the areas lacking in finds compared with Nottingham Green Glaze. Red lines are postulated tracks. Black triangles are pits with no finds of this type.

RECOVERY FROM THE BLACK DEATH

Light-bodied Gritty Ware was gradually replaced by Midland Purple Ware,

which is usually said to have appeared at around 1380. It is likely that it

was being made in Ticknall in south Derbyshire and marked a move for pottery

making in the East Midlands away from Nottingham. Midland Purple Ware was the

commonest pottery that was collected from this period, but several of the lesser

medieval fabrics, particularly the shelly wares, had long date ranges that continued

on to 1500.

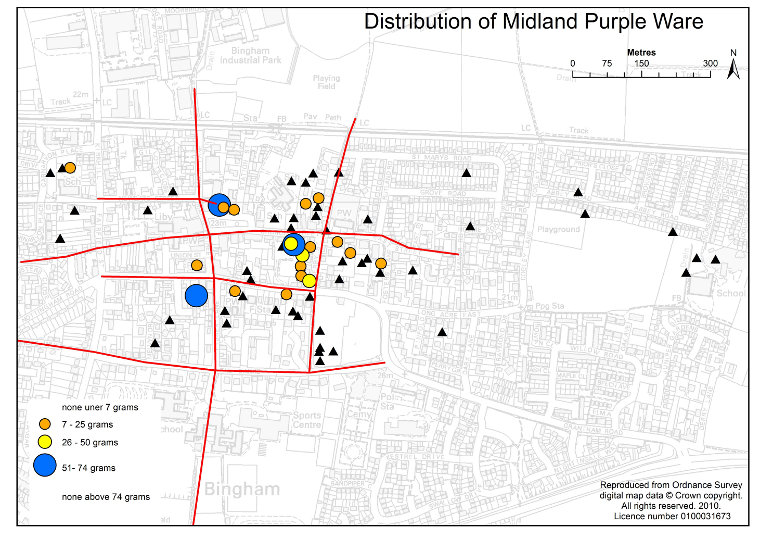

Fig 20 Map showing the pits with Midland Purple Ware in them. Red lines

are postulated tracks. Black triangles are pits with no finds of this type.

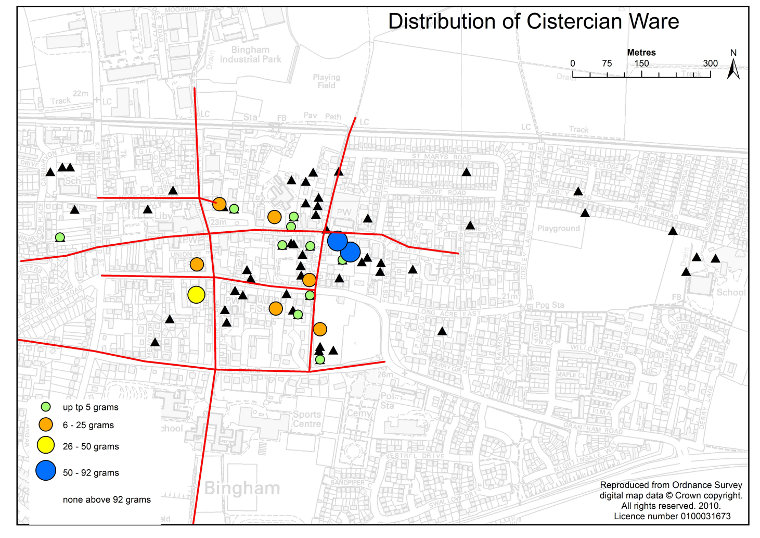

Fig 21 Pits containing Cistercian Ware. The finds near the mill site on Tithby road confirms the presence of this road at that time. Red lines are postulated tracks. Black triangles are pits with no finds of this type.

Light-bodied Gritty Ware was gradually replaced by Midland Purple Ware, which is usually said to have appeared at around 1400 lasting at least until c1500. It is likely that it was being made in Ticknall in south Derbyshire and marked a move for pottery making in the East Midlands away from Nottingham. Midland Purple Ware was the commonest pottery that was collected from this period, but several of the lesser medieval fabrics, particularly the shelly wares, had long date ranges that continued on to 1500.

The first properly glazed earthenware to be made anywhere in England was Cistercian Ware. This was generally dark brown, almost black, and though the glaze was pitted, sand speckled and occasionally incomplete it was on both the inside and the outside of the vessel. It was made in Ticknall from after 1450, running concurrently with Midland Purple Ware for over half a century.

Records reported in Bingham Back in Time by Allen, Ashton and Henstock, indicate that in the 1440s the tax rebates allowed in Bingham manor were just over 6% and in 1450 the list of holdings within the manor made no mention of decayed properties. The implication from this is that Bingham had largely recovered from the effects of the Black Death by then.

Using the same groupings of pits as in Table 1 the first appearance of both Midland Purple Ware and Cistercian Ware is shown in Table 2.

Seven of the sites that had yielded Light-bodied Gritty Ware also had Midland Purple Ware. This might imply continuity because there is an element of overlap in the date ranges for the two. Two places with Light-bodied Gritty Ware (CB25 and SHC05) had neither Midland Purple Ware nor Cistercian Ware implying that these places became inert at the end of the 14th C or thereabouts.

Only three of the areas that had a pre-1350 assemblage yielded either Midland Purple Ware or Cistercian Ware. These are Warner’s Paddock, Robert Miles Junior School and Long Acre LA04, though LA30 in Long Acre has nothing younger that Nottingham Green Glaze Ware. The Old Post Office (LA23) showed both of these as the earliest recorded finds.

From these results it is possible to conclude that activity continued to cease,

apparently permanently, in some areas late in the 14th C. Where there had been

an early end to activity on a site; that is there is no post-1350 medieval pottery

at them, there was a time gap of at least 50 years

before any of the land came back into use. This supports the documentary evidence,

but it also shows that while there might have been overall recovery, there were

certain areas, which had sustained a population within the town, that never

recovered.

TABLE 2

| Pit Area | Pit numbers | LBGW | MP | Cistercian Ware |

| Market Place |

CB01, 01E,01A, CB34,35 | X | X | X |

| Church Lane |

CB14,15,19,33 | X | X | |

| Cherry St |

CB06,17,21,LA09,12 | X | X | X |

| Rectory |

CB07, 11,20 | X | X | X |

| Bingham Infants |

SHC01, 02, 03 | X | X | X |

| Church St |

CB22, 27 | X | X | X |

| Newgate St |

CB25 | X | ||

| 24,Long Acre |

LA07 | X | X | X |

| Warner’s Paddock |

LA06,15, 24, | X | X | |

| Robt Miles Jun |

CB02, 04 | X | ||

| Carnarvon Sch |

CCLM04, 05 | |||

| Fisher La |

LA11 | |||

| Foster’s La |

CB12,23,24 | |||

| Long A East |

LA14 | |||

| 50,Long Acre |

LA04 | X | X | |

| 79,Long Acre |

LA13 | |||

| 8 East St |

CB32 | |||

| Rutland Rd |

CB31 | |||

| The Paddock |

LA19 | |||

| 10, Newgate |

CB26 | X2 | ||

| Fairfield St |

SHC05 | X | ||

| Old Post office | LA23 | X | X | |

| Tithby Rd Mill |

W01 | X |

LBGW Light-bodied Gritty Ware

MP Midland Purple Ware

X2 This is NLBGGW with a date range of 1375-1400

BINGHAM’S STREET PLAN

In his study on medieval new towns Professor Maurice Beresford (New Towns of

the Middle Ages: Town Plantations in England, Wales and Gascony, 1967 , 670pp)

lists 172 new towns that were established between 1066 and 1370. The peak of

their development is the 13th C. Not all of them actually developed into new

towns. Some having been given the template did not progress to full development.

The layout of Bingham as shown on the conjectural map for 1586 is so clearly

influenced by the new town model that it is tempting to suggest that it is one

that was planned.

Beresford’s original concept applied to new towns that had been planned or “planted” in the medieval period. However, Gill Stroud (in Stroud, G. 2002. Nottinghamshire Extensive Urban survey: Archaeological Assessment: Bingham. Notts County Council & English Heritage) suggested that in Bingham the new town model may have been imposed on an original layout that had developed organically. She suggested that the planned arrangement had been implemented in two phases, the first in the 11th or 12th centuries. In this model the main street would be Long Acre and Long Acre East. The Banks would be the southern back lane and East Street and Church Street the northern back Lane. Streets like Foster’s Lane, Fisher Lane, Jebb’s Lane and Market Street were all cross lanes. Perhaps as importantly, the land in the town would have been divided up into more or less equal sized plots stretching from the main street to one of the back lanes. This pattern of streets and land division is recognisable on the 1586 map in relation to plots between the main street, Long Acre, but then called Husband Street, the common name given to a street along which farmers lived, and the southern back lane, now The Banks. It is not evident between Husband Street and the northern back lane. Most of the cottagers lived on the northern back lane in 1586 and developments around the market place had taken some of the land from plots to the south. This could be explained by Stroud’s suggestion that the second phase of development of the street plan was in the 13th C when the new market place, adjacent fairground, new manor house and manorial chapel were developed and the new axis for the town became Church Street, Market Place and Newgate Street. She compared Bingham with other Nottinghamshire towns such as Beeston, Beckingham and Farnsfield.

The archaeology as shown in the test pits suggests an alternative development for the street plan.

Iron Age and the later Roman Bingham consisted of a settlement largely to the south of the church stretched out along the line of Jebb’s Lane and Cherry Street. This north-south alignment could have extended along Church Lane. Beyond the northern end of Church Lane a path would have linked the Bingham houses to the Iron Age and Roman settlements known to have been on Parson’s Hill. There is a possibility of a track in Roman times eastwards from near the church to the Roman villa at Carnarvon Primary School, but a parallel one to this starting from the Cherry Street Roman house and following what is now Long Acre East towards the Roman villa is probably more likely. During the Early/Middle Anglo-Saxon period there are clear indications from the test pits of the possibility of habitations near the Market Place and at the back of the Chesterfield Arms suggesting a track from there to the site of the church. Christianity came to Mercia in the 7th century. Thus, for the early history of Bingham four of the roads that made up the postulated planned village probably already existed.

This simple arrangement persisted until the end of the Middle Anglo-Saxon period. Though there is no evidence from the test pitting that can be used to say when open field farming came to Bingham there is a likelihood the Anglo-Saxon pattern of self-sufficient agriculture changed to widespread arable cultivation at the time of village nucleation. The conjectural map for 1586 shows that the main open fields were all in the southern half of the parish with the road now called The Banks running east-west along the northern edge of them. It is suggested that this road was present for access to the fields from the Middle Anglo-Saxon period.

This means that both the northern and southern back streets in the planned

village, the eastern end of what became known as Husband Street and one of the

important cross lanes were in existence long before Norman times.

During this early period Warner’s Paddock and northwards to the church

appears to have been the dominant place in the Bingham settlement, but it is

during the time when Nottingham Splashed Ware was commonly in use (1100 to 1250)

that Warner’s Paddock reached the climax of its development. Thereafter

the centre of Bingham shifted to the Market Place, which is consistent with

Stroud’s suggestion that there was a major development phase in the 13th

C, though it might have happened earlier, in the late 12th C and earlier than

the arrival in Bingham of Sir Richard de Bingham. It is also likely that the

cross lane that is now represented by Market Street and Fisher Lane came into

existence at this time

The remaining part of the planned layout is the main street. Called Husband

Street in 1586 it was where most of the farmers lived at that time. Seven test

pits were dug on both sides of Long Acre that were not close to any junctions

with cross lanes. No pottery was found in any of the Long Acre test pits older

than Nottingham Splashed Ware, which was the most abundant of the marker fabric

types we use in the medieval period. This might suggest that Long Acre was laid

out in Norman times. However, the four test pits along Long Acre that were close

to cross roads showed nothing older than mid 13th C and the total number of

finds of medieval age in the Long Acre pits was very small, with no more than

four in any pit; thus all of them could be explained as a component of manure

scatter.

Field walking evidence suggests that after village nucleation in the late 9th

century farmers returned to live at the margins of the parish in the 12th or

13th centuries and did not return until after the Black Death. Thus Long Acre

(or Husband Street) may not have been populated at all during this period. There

is a slight suggestion in the alignment of the pits with Nottingham Splashed

Ware along Long Acre that this road may have been in existence in the 12th century,

but no one lived along it after that. Using the appearance of Midland Purple

Ware it seems that that there may have been a return to Long Acre in the 15th

century, but the strongest evidence of occupation is shown by the appearance

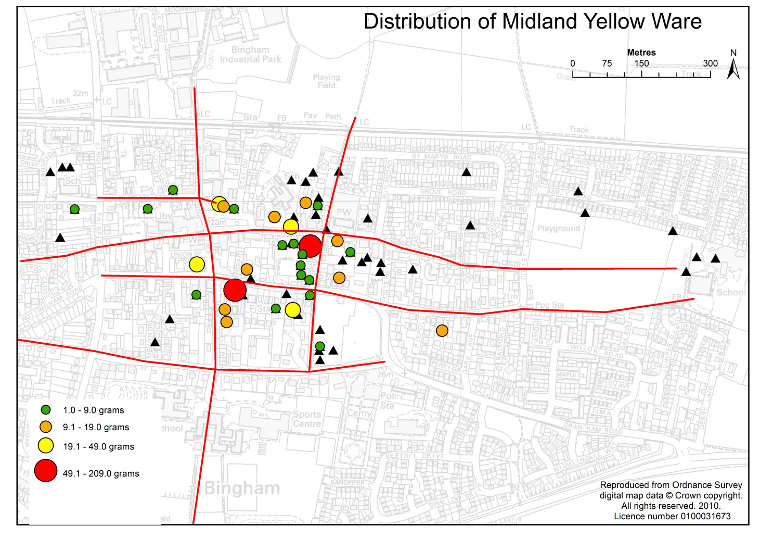

of Midland Yellow Ware in the late 16th century

The layout of the streets in Bingham can be explained primarily by organic growth, but the influence of topography and geology with its east-west grain is also important. The evolution of the street pattern can be summarised as follows:

- The eastern cross lane now represented by Jebb’s Lane, Cherry Street, and Church Lane originated in the Iron Age and remained one of the main tracks through the growing settlement and, later, village until the Norman Conquest.

- A track from the area of the church to the Roman villa in Carnarvon Primary School, which is the eastern extension of the northern back street existed from Roman times or earlier.

- Parallel to this a track from the Roman house at the southern end of Cherry Street along Long Acre East to the villa probably also existed in Roman times.

- The road from the church towards modern Newgate Street came into prominence in Middle Anglo-Saxon times.

- Also in Middle Saxon times the east-west road now called The Banks, but which fits the role of the southern back street in 1586, was used as the access road from the village area around Warner’s Paddock to the open fields. The Banks runs along the foot of a steep rise trending east-west and could be in no other position.

- The western cross lane now represented by Market Street and Fisher Lane came into existence in the 13th century primarily as an access road linking the habitations around the Market Place, now the centre of Bingham, to the open fields.

- The road west from Market Place may have been there as an access road to fields in Roman times came into prominence in the early 14th century when Sir Richard de Bingham consecrated his personal chapel situated near the junction of present-day School Lane and Fairfield Street.

- Long Acre, called Husband Street in 1586, may have existed as early as the 12th century, but cannot be shown to have existed as a road significantly before the late 16th century. The oldest pottery found along it is 12th century, the same as Fisher Lane. If there had been a road here it is likely to have been set in the 12th century, before Sir Richard de Bingham came to live in the parish, but it did not become a significant road until the 15th or 16th centuries. Most of the development of Bingham that can be attributed to Sir Richard is between the Market Place and the church.

POST-MEDIEVAL DEVELOPMENT

This is the period from the late 15th century and c1750 when mass production

started in the ceramics industry in Stoke on Trent. There are, however, overlaps

at both ends and both Midland Purple Ware and Cistercian Ware came into production

in the late medieval period extending into the early post medieval.

Using the weight per pit of finds for each of these as a starting point it is evident that the core of Bingham, as it recovered from the Black Death, had contracted considerably and that the centre had shifted to the west. The main focus was on Cherry Street, the area around the modern rectory and along Church Street to the Market Place. Robert Miles Junior School, which had shown nothing since Nottingham Reduced Green Glazed Ware, probably dating to the mid 14th C, began to show again with Cistercian Ware. This area lies between the Church Street pits and the Market Place, but is also thought to have been the site of the medieval rectory.

Fig 22 Location of pits with Midland Yellow Ware showing the roads as it is conjectured from the pits finds distribution. Red lines are postulated tracks. Black triangles are pits with no finds of this type.

Two other places are of significance. These are pit LA07, which is close to the old Wheatsheaf pub and the old post office (LA23), which is opposite the pub. These sites lie on the road south from the market place, but also the pub is thought to have existed on this site at least since 1586. Another interesting site is LA04 on Long Acre. This is on the site of the long-demolished pub The Granby Arms. Research done for the 1586 map shows that there were freeholds along Long Acre westwards from Jebb’s Lane right to the site of The Granby Arms, but not including it. The possibility exists that these were long established and present during the late medieval/early post medieval period.

TABLE 3

Weight in grams of finds from each of the pit areas

| Pit area |

Pit numbers | Midland Purple Ware | Cistercian Ware | Midland Yellow Ware | Slipware |

| Market Place |

CB01, 01E, 01A, CB34,35 | 122 | 54 | 1491 | 114 |

| Church Lane |

CB14, 15, 19, 33 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 54 |

| Cherry St |

CB06,17,21,LA09,LA12 | 128 | 16 | 138 | 89 |

| Rectory |

CB07, 11,20 | 40 | 166 | 22 | 81 |

| Bingham Infants |

SHC01, 02, 03 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Church St |

CB22, 27 | 22 | 5 | 61 | 64 |

| Newgate St |

CB25 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Long Acre Henstock |

LA07 | 64 | 28 | 9 | 0 |

| Warner’s Paddock |

LA06,15, 24, | 0 | 14 | 1 | 0 |

| Robt Miles Jun |

CB02, 04 | 0 | 9 | 13 | 17 |

| Carnarvon School |

CCLM04, 05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fisher Lane |

LA11 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| Foster’s La |

CB12, 23, 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Long Acre East |

LA14 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 |

| Long Acre Harland |

LA04 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 17 |

| Long AcreHanmer |

LA13 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 29 |

| 8 East St |

CB32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| Rutland Rd | CB31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 46 |

| The Paddock |

LA19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| 10, Newgate |

CB26 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| Fairfield St |

SHC05 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 9 |

| Old Post Office |

LA23 | 11 | 15 | 44 | 65 |

| Tithby Rd Mill |

W01 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

Expansion of Bingham did not significantly begin until the 16th C. This is illustrated by comparing Midland Purple Ware (c1400 to c1500) and Midland Yellow Ware, which was being made in Ticknall from the second half of the 16th C. The younger ware type also shows just how the focus for the town had shifted westwards and the old north-south linear village had gone. Long Acre also had come into prominence.

Slipware came in a century later than Midland Yellow Ware (late 17th to mid/late

18th C). Isolated occurrences are more likely to indicate manure scatter on

arable land than settlement, but Midland Yellow Ware appears to start a trend

in Church Lane area, on Newgate Street at

the top of Gillott’s Close and on Long Acre at LA13.

All of these sites confirm localities shown with homesteads on the 1586 conjectural

map. By this time there were farms and cottages along Long Acre and Long Acre

East from close to the site of the present-day White Lion pub to the eastern

end of Long Acre East. This was then called Husband Street

and was the main road through Bingham. Parallel to it to the north was Newgate

Street, the Market Place, Church Street and East Street, along which were cottager

households. The finds in the test pits confirm all of these conjectures.

From then on the growth of Bingham can be charted with documentation.